Brinda Karat’s Hindutva and Violence Against Women came at peak polling time, when every day brought with it an unsettling feeling that members of the ruling party would say something so nasty, we wouldn’t be able to heal from the wounds. The “mangalsutra bhi bachne nahin denge (‘they’ will not let even your mangalsutra go)” comment by Prime Minister Narendra Modi was blame twisted so out of shape, it pegged imagined future crimes on a Muslim minority whose women had in fact suffered at the hands of Hindutva, as the book proves.

In fact, a small part of the 90-page monograph talks about “the demonisation of Muslim men” being an “important aspect of the Hindutva project”, as she explains in this interview. Love jihad, for instance, “targets the Muslim male in a consensual inter-community relationship, and equally denies an adult Hindu woman her right to self-choice,” the book says.

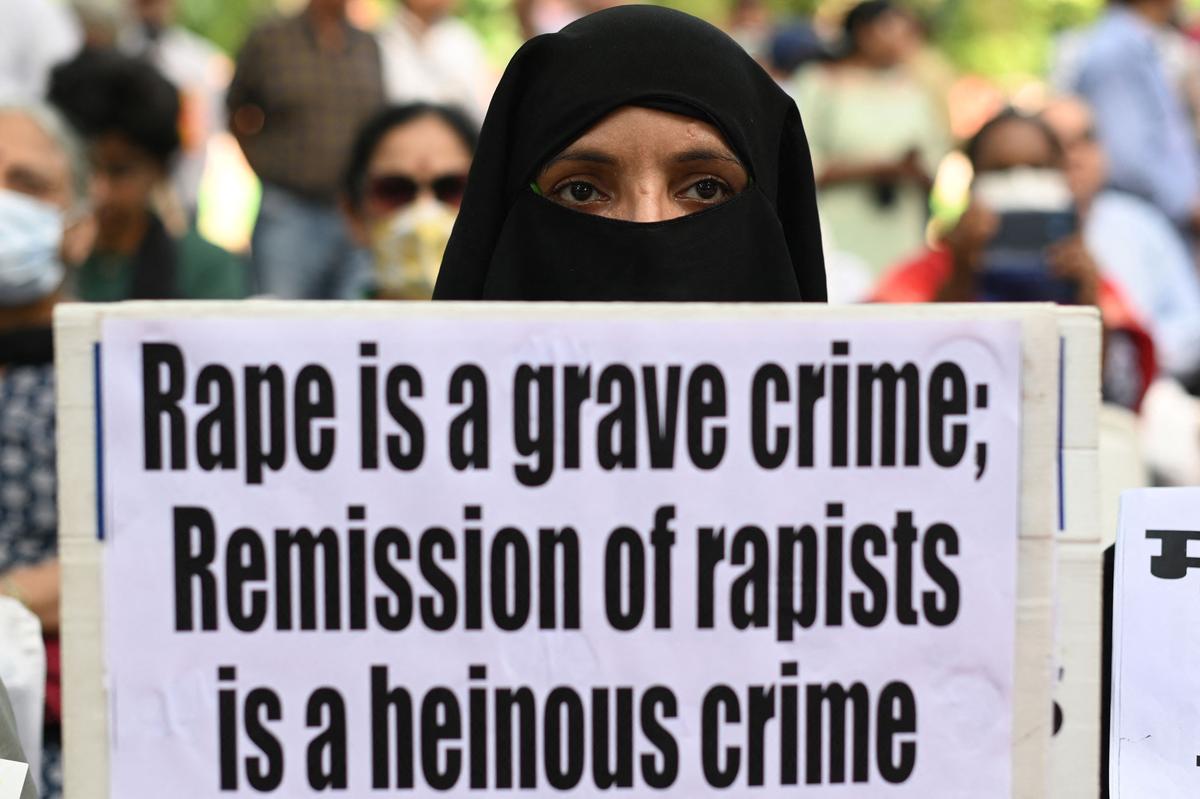

A demonstrator holds a placard at a protest seeking justice for Bilkis Bano, in New Delhi. | Photo Credit: Getty Images

To bolster the premise of her book, Karat cites various cases, from Bilkis Bano’s ordeals in Gujarat from 2002 onwards and the 2018 rape of a child in Kathua in Jammu and Kashmir, to the sexual violence the Kuki-Zomi tribal women faced during the Manipur violence and the fight India’s women wrestlers are still putting up. She weaves in crime data, court orders and observations, with commentary, reminding the reader of events forgotten, like the 2020 Hathras caste atrocity. She also gives context, quoting politicians who supported violence and a subversion of justice. Edited excerpts:

Artists portray the increasing atrocities on Dalit women highlighting the Hathras rape case, in New Delhi. | Photo Credit: Getty Images

The title is about women, but you talk about different groups of marginalised people: Dalits and Muslims, for example. Why was this?

The central point of this essay is not just the increase in cases of brutal violence against women over the last 10 years. We have seen horrific cases earlier too. To me, what is striking is that the government in power and dominant forces look at violence against women dictated by a changing framework which has two interlinked aspects — communal and Manuvadi majoritarianism — where the processes of justice get subverted. The approach is determined not by the need for justice for the victim, but it depends on the religious or caste identity of the victim and the perpetrator. This is my basic premise, and I link this with Hindutva’s approach to women. If the perpetrator happens to be Muslim, the entire Hindutva ecosystem is driven to select those cases of rape and sexual violence to talk about. If both the perpetrator and the victim belong to the majority community, it is the woman who is blamed, particularly if she belongs to an oppressed caste.

The subtext through the book suggests that Hindutva stands for violence and lies and a subversion of justice. Did you read a great deal before you wrote the essay?

I would not call this an academic work, where there was a lot of reading and referencing. This essay came out of what I was viewing as a person deeply involved in struggles of women against violence. My publishers [Speaking Tiger] commissioned this, and we had many discussions. The subject was very much on my mind; there was a seed, and after my discussions with them, I wrote it on the go. There were a couple of months of working and reworking.

A person keeps a photograph of Shraddha Walkar on the dais during Beti Bachao mahapanchayat in New Delhi. | Photo Credit: Getty Images

What aspects of violence against women should we be particularly cognizant of?

Change is so under the surface that we don’t really see it and identify it until it hits us in our face. Take the Shraddha Walkar case [where a 27-year-old woman was brutally murdered allegedly by her live-in partner who had also subjected her to abuse]. The case throws up other issues: of a woman’s autonomy, the strength she should get from society, the reasons a woman doesn’t walk out of a violent relationship, social stigmas involved. You have to provide a social infrastructure for a woman to transform from a victim to a survivor. But in her case, all that was seen was the religion of the perpetrator. It’s extremely important to understand where we are and where we should be going. The current talk of naari shakti (women’s strength) is deafeningly silent on issues like domestic violence, dowry deaths. In the last 10 years there have been over 70,000 deaths of women linked to dowry and domestic abuse, but this is not considered an issue. I link this to what a woman’s place is in the Hindutva framework.

Considering we often speak in echo chambers, do you fear the book will only be read by those interested in feminism?

I do hope it will reach a larger audience. I would think there is an interest among young women who are grappling with some of the difficult situations [in the book] and this discussion may help. I certainly hope it does become accessible to women. It is important for young women to know the wider issues that are impacting their day-to-day lives.

People of Kuki, Zomi and other tribes staging a protest at Jantar Mantar, New Delhi, against violence in Manipur. | Photo Credit: Sushil Kumar Verma

While all the incidents in the book are both heinous and heart-wrenching, which impacted you the most?

I cannot pick one, they all had a huge impact, but I do remember the 19-year-old tribal Christian girl in Manipur who saw her father and son killed in front of her eyes and was then stripped and gang raped; later that video was seen across the world. I cannot forget her courage and dignity. The fact that after that horrendous sexual violence, she kept silent about it for days. She couldn’t share the horror for days, even with her own mother, who was grieving for the loss of her husband and son. This speaks of our lack of structures, which should immediately get activated in such terrible times. That girl — her silence spoke to me more than any words; she was so alone in her experience. And in addition, the people most beloved to her, her father and brother, were murdered trying to protect her. That struck me as being one of the most cruel things — that you are so alone in your experience. She later got the support of Kuki-Zomi women’s groups who have done whatever possible to help. But from the government’s side, there’s no movement forward to bring justice; the members of the mob are still free.

When you write an essay like this, there are obviously going to be a lot of emotions you go through. Could you talk a bit about those?

Over the years working with women, the kind of trauma and struggle every woman who has ever faced violence, their strength and courage, the fight for justice by women’s organisations is deeply embedded in my own work and thinking. There’s an emotional response yes, anger; but also thinking and trying to find ways to change this. The approach of collective struggle is critical.

Hindutva forces take out a rally in Navi Mumbai. | Photo Credit: Getty Images

Now that we see the third term of the BJP and its supporters, how do you see this term panning out in terms of violence and vitriol?

I don’t think we can gauge the deep penetration of Hindutva by just a vote count. The leopard does not change its spots. But I feel we do have space for discussions and for a rejuvenated movement; we just need to fight consciously to take forward people’s resistance as reflected in the setback suffered by the Hindutva forces in these elections.

Hindutva and Violence Against Women; Brinda Karat, Speaking Tiger Books, ₹450.

sunalini.mathew@thehindu.co.in

Published – June 21, 2024 09:01 am IST