An eye emergency led historian Josephine Quinn to ponder over what she wanted to say in her next book. “I thought what if I lose my vision… and decided to summarise my learning from teaching history for two decades.” How the World Made the West is an ambitious book, which moves away from a narrative focused solely on the Greeks and Romans, to conclude that their histories are rooted in other places and even older peoples. On the sidelines of the Jaipur Literature Festival, Quinn explained why connections, not civilisations, drive historical change. Edited excerpts:

Statue of ancient Greek philosopher Plato in Athens. | Photo Credit: Getty Images/iStockphoto

Why are you convinced that a narrative of the past focussed only on the Greeks and Romans impoverishes an understanding of the world?

After teaching about Greece and Rome for 20 years, I was convinced that everyone, and particularly my students, are being shortchanged by the focus solely on the Greeks and Romans to the exclusion of other cultures and peoples. I wanted to tell a bigger story, about the connections they had with other people and civilisations. My own guides in this are the Greek and Roman authors themselves because they were so interested in these connections. Plato, for example, writes that astronomy, philosophy, mathematics, and history all go back to other cultures. The Greeks imported law codes and literature from Mesopotamia, stone sculpture from Egypt, irrigation from Assyria and the alphabet from the Levant.

Illustration of a Trireme, an ancient galley by Phoenicians, Greeks and Romans. | Photo Credit: Getty Images/iStockphoto

Why have these millennia of interaction largely been forgotten?

In Europe, particularly, there is a strong focus on the Greeks and Romans alone. I trace it back to the 18th century when the concept of civilisation first came into being. Ideas developed in the Victorian period then organised the world into ‘civilisations’, separate and often mutually opposed, and it has been extremely damaging to the way people think of the world they are living in, and of the past. If we can get over that, we can go back to an ancient world, and not only to the Greeks and Romans but also other cultures, and see the bigger connections.

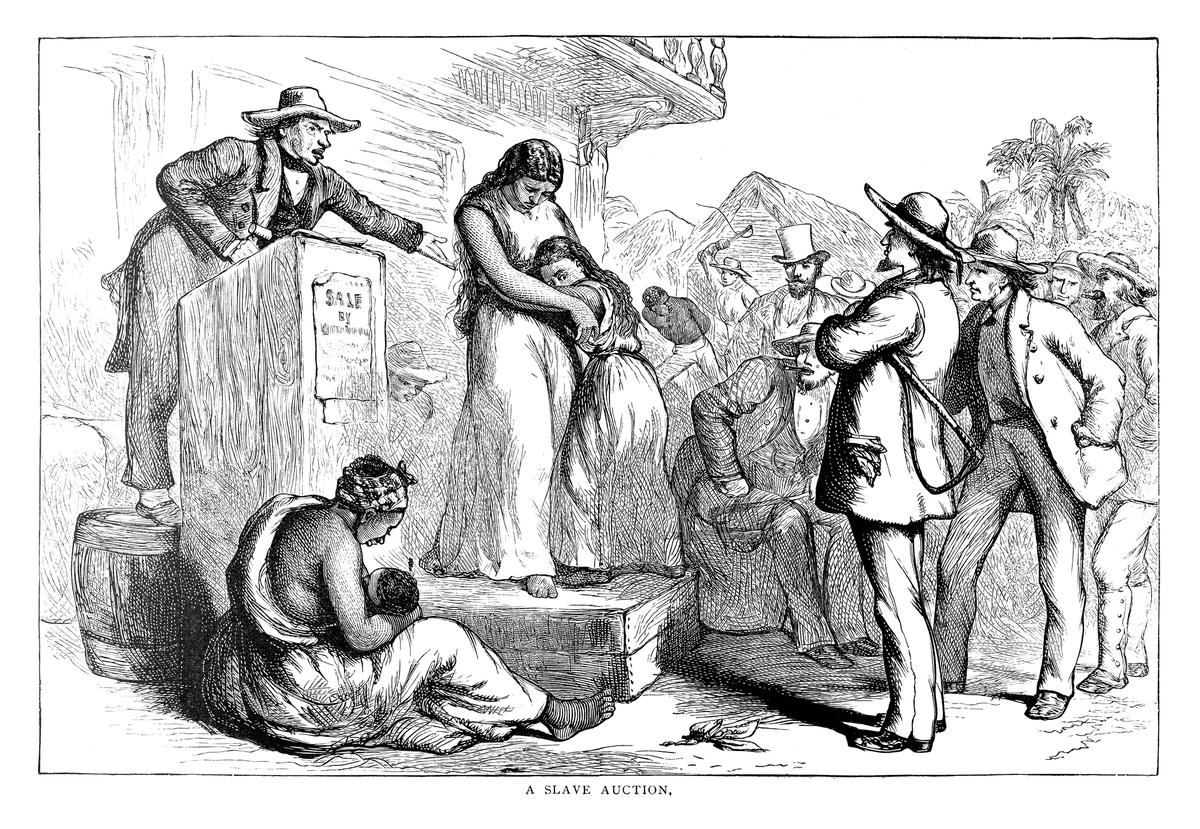

Slave auction | Photo Credit: Getty Images/iStockphoto

You found an interesting detail on slavery.

Scholars often identify classical Greece as the first true ‘slave society’. But when I was researching the book, I found slavery went further back. The Phoenicians, for instance, were moving people around — that kind of dependence of the economy on slave labour actually goes back to at least 1000-900 BCE, and probably started in the western Mediterranean. Interestingly, the colonists — the first people who were settling from the Levant in the western Mediterranean were also the first people who were introducing enslavement.

Antique illustration of coffee harvesting depicting a slave with his owner. | Photo Credit: Getty Images/iStockphoto

Slaves too tell stories…

Yes, the thing about slavery is that of course slaves are real people and they tell stories too and so stories are moving around with them, ideas are moving around the Mediterranean and beyond. They are talking to each other, and they are talking to their masters. There’s always communication even if a class system somewhere or a caste system elsewhere tries to fit people into neat categories.

Etruscan artifacts in British Museum, London. | Photo Credit: Getty images/istock

Did the concept of civilisation provide useful support for western European imperialism?

The European idea of civilisation was first born as an excuse and cover for imperialism. It began with the belief that civilised societies had a duty to help less developed ones gain freedom and sovereignty, and that despotism was a legitimate form of government in dealing with “barbarians, provided the end be their improvement.” By the 1820s, French historians like Francois Guizot began to use civilisation in the plural, to refer to civilisations that preceded the European civilisation, showing particular interest in the Indians, Etruscans, Romans and Greeks, among others. But the problem was that it created an idea that the civilisations were cut off from each other, separate. Their focus was on identifying and ranking individual societies’ inherent cultural traits rather than on their progress towards a shared human ideal. Cultures on this view were not only quite separate from one another, but had natural ceilings to their development. Over time, this helped to justify harsher forms of imperial rule.

So, you argue that civilisational thinking misrepresents history…

Yes, because it is not peoples that make history, but people, and the connections that they create with one other. Human society is not a forest full of trees, with subcultures branching out from single trunks. It is more like a bed of flowers, in need of regular pollination to reseed and grow anew, as ecologist Eric Sanderson told me. Distinctive local cultures come and go, but they are created and sustained by interaction — and once contact is made, no land is an island. There has never been a single, pure Western or European culture. So called western values like freedom, rationality, justice and tolerance are not originally western, and the West itself is in large part a product of long-standing links with a much larger network of societies, to south and north as well as east.

Steppe landscape | Photo Credit: Getty Images/iStockphoto

How did sea journeys and riders on the Steppes expand the movement of people and ideas?

The civilisational way of thinking is not working, and that’s the argument I make in the book. From a western point of view, Europe was essentially cut off before around 2000 BCE because there weren’t efficient ways of getting there. The people in the Steppe were already moving around, and after the wheel was invented 5000 years ago, goods began to be moved too. And at the same time sailing was invented in the Nile. But the huge changes that happened in the second and first millennia BCE were that first of all the Steppe riders began to make longer journeys to and fro by land on horses, creating a reliable route into the great Hungarian plain, and that encouraged consistent contact — we are not talking about a sole explorer or two. And once Egyptian sailors invent the technology to go into the open sea, then that becomes another much faster way of interacting by sea. Europeans were suddenly introduced to the world.

Supporters of French far-right, in Henin-Beaumont, northern France. | Photo Credit: AP

How the World Made the West; Josephine Quinn, Bloomsbury, ₹699.

sudipta.datta@thehindu.co.in