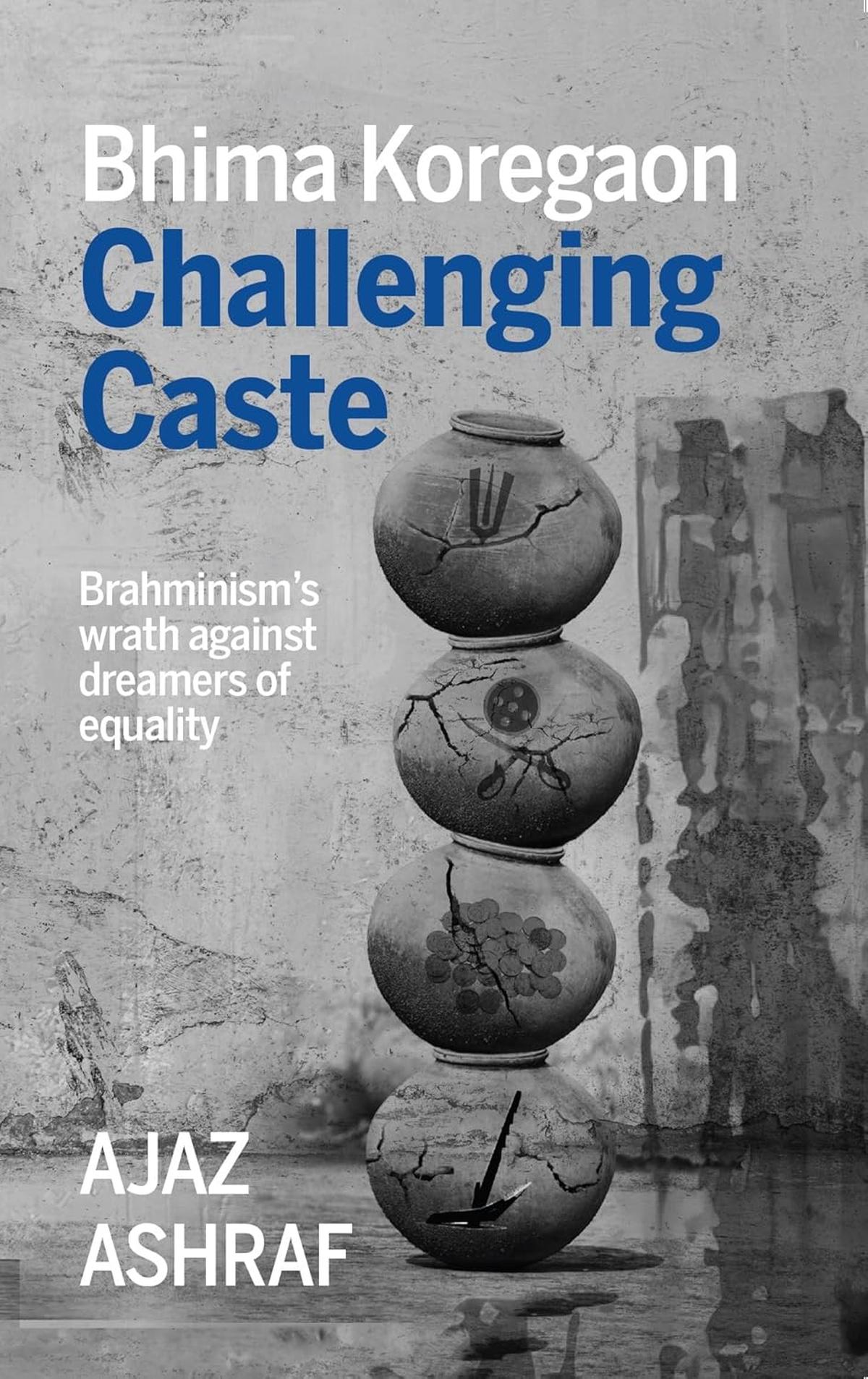

In Bhima Koregaon: Challenging Caste, senior journalist Ajaz Ashraf relooks the events that led to the Bhima Koregaon violence on January 1, 2018. Ashraf sees the incident as a clash between two worldviews, one striving to flatten the social hierarchy and the other perpetuating it, as he says in this interview.

Dalits sitting by wall paintings of Ambedkar and Periyar, both famous for their fight against discrimination. | Photo Credit: Getty Images

You recreate the Bhima Koregaon violence from varying points of view. How difficult was it to write this book?

The difficulty arises from different castes remembering a shared past differently. For instance, Dalits celebrate the 1818 Battle of Bhima Koregaon as they believe the British Indian Army’s victory over the Peshwa liberated them from his oppressive Brahminical rule. Mahar soldiers played a significant role in the battle. But this belief is a myth, it is argued, for the British fought the Peshwa to expand their empire, not to liberate the Dalits.

Now, consider this: in 1786, the Peshwa rejected the demand of Konkan’s Mahars that Brahmin priests should conduct their marriages. Their quest for equality was suppressed. Wouldn’t they have been relieved, if not delighted, at the demise of the Peshwa rule 32 years later?

In Kurosawa’s Rashomon, eyewitnesses to a murder provide remarkably different accounts of it. This is as true of the accounts of four police officers and two Dalits I used to reconstruct the January 1, 2018, violence at Bhima Koregaon. The officers did not hear the insulting, provocative slogans the two Dalits did regarding their community. Whose narrative is authentic? The violence, to me, seemed scripted against Dalits. ‘Seemed’, don’t miss that.

A gathering at Bhima Koregaon war memorial in Pune. | Photo Credit: PTI

When did Bhima Koregaon become a site of annual pilgrimage?

The tradition of Dalits gathering at Bhima Koregaon is popularly ascribed to B.R. Ambedkar, who visited the village on January 1, 1927. January 1 is the day the Peshwa was defeated in 1818. But Ambedkar was taken there by Dalit leader Shivram Kamble, who had been assembling community members every New Year’s Day for some years before 1927. It was Kamble’s method of reminding the British about the contributions of Mahar soldiers in the Battle of Bhima Koregaon, and persuade the colonial power to reverse its 1892 policy of not recruiting them for the Army. However, it was from the 1980s that thousands upon thousands of Dalits began visiting Bhima Koregaon. The celebration today invokes the memory of 1818 to inspire Dalits to fight caste oppression.

A BJP supporter holds up an image of Ambedkar during Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s rally at Ramlila Maidan in New Delhi. | Photo Credit: Getty Images

Can you tell us about the trigger for the violence?

On the night of December 28-29, 2017, Dalits erected a board outside the precincts of the samadhi of Chatrapati Sambhaji, located at Vadhu Budruk, a village three kms from Bhima Koregaon. The board recalled that after Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, on March 11, 1689, ordered the execution and dismemberment of Chhatrapati Sambhaji, his body pieces were scattered. The board claimed that Govind Gopal, a Mahar of Vadhu Budruk, collected the pieces of his body, stitched them together, and cremated him.

Maratha residents of Vadhu Budruk, on December 29 morning, uprooted the board, and desecrated the samadhi of Govind Gopal, also located in the same village. They said the board was propagating wrong history, claiming it was a Shivale-Patil couple, Maratha by caste, who had cremated Chhatrapati Sambhaji. This is mentioned in another board at the samadhi, but it was erected only in 2015, after an existing board was removed.

The pre-2015 board credited the entire village with cremating Chhatrapati Sambhaji, and his son Chhatrapati Shahu I for building the samadhi. The pre-2015 board named Govind Gopal as one of the “three servants” of the samadhi, and said it was “significant” that he belonged to the Mahar caste. The 2015 board, erected allegedly by Milind Ekbote’s outfit, omitted the reference to Govind Gopal, an obvious attempt to efface him from popular memory, from history.

The news of the desecration of Govind Gopal’s samadhi went viral on social media. Seven Marathas were arrested. The mounting tension between the two castes was exploited to foment violence on January 1.

But the fight over history continues: the Bhima Koregaon Commission of Inquiry was presented a copy of a purportedly British era document that claimed Chhatrapati Sambhaji was cremated by Bapuji Shivale and Padmavati, the Shivale couple. I found several discrepancies in this document. In contrast, there are official documents testifying to Govind Gopal’s links to Chhatrapati Sambhaji’s samadhi, but none supporting the claim that he cremated him. On balance, Govind Gopal has a stronger link to the history of Chhatrapati Sambhaji than Vadhu Budruk’s Shivales.

After the 2018 incident, has the commemoration of the Battle of Bhima Koregaon stopped?

It remains an annual affair, and will continue to be so because Dalits, by remembering Bhima Koregaon, lay claim to history, of being not just hapless untouchables but having played a significant role in the demise of the Peshwa’s Brahminical rule.

Bhima Koregaon: Challenging Caste; Ajaz Ashraf, Authors Upfront, ₹795.

sobhanak.nair@thehindu.co.in