The story so far:

The ambitious plan to build a mega-hydropower dam across the Brahmaputra at the Great Bend region of the Medog county in the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR) in China, has been in the drawing boards of Chinese hydrocracy for decades. The clearest signalling to this effect happened in 2020 when this project was included in China’s 14th Five-Year Plan. Its approval was granted on December 25, 2024. India, Bhutan and Bangladesh will have serious downstream implications of this 60 GW hyper-dam built upstream by China.

Where is this project?

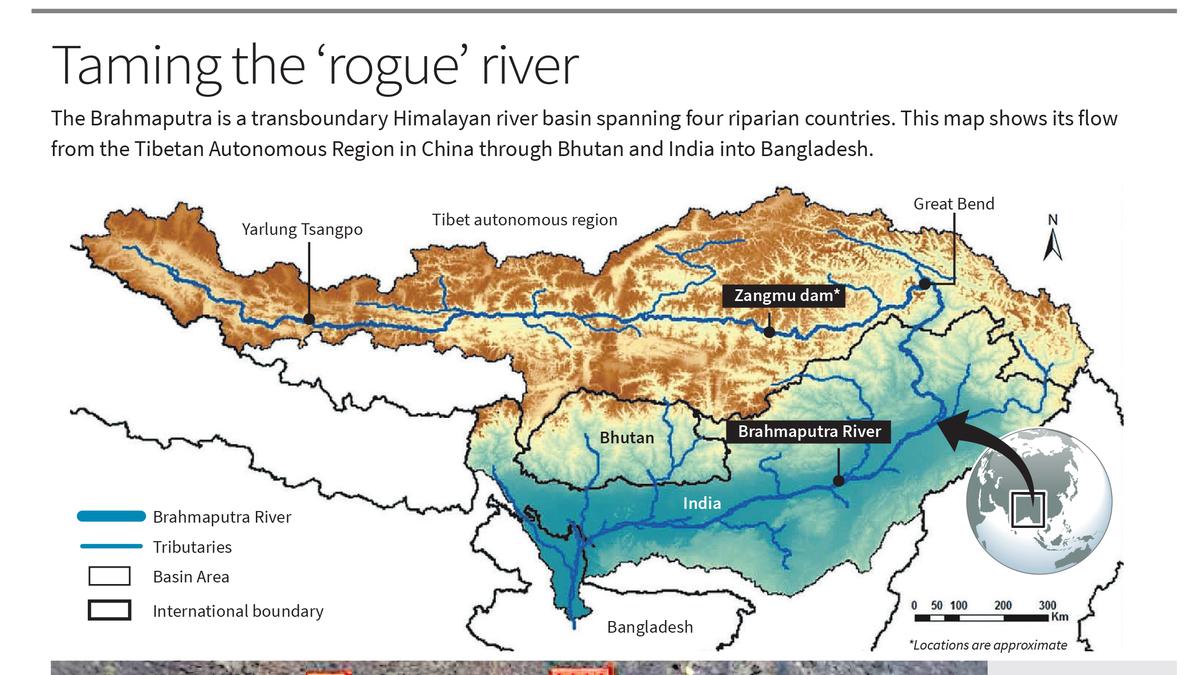

The Brahmaputra is a transboundary Himalayan river basin spanning four riparian countries. China is the uppermost riparian nation with the river system originating in the TAR, where it is known as the Yarlung Zangbo (or Tsangpo). India and Bhutan are lower riparian nations in relation to China and middle riparian countries in relation to Bangladesh. It is from Bangladesh, which is the lowermost riparian nation, that the river drains into the Bay of Bengal. All riparian countries have major water infrastructure projects planned in the river basin, such as hydropower dams, embankments meant for river control, irrigation dams and barrages.

Is the Brahmaputra river basin trapped within nation-states?

Transboundary river systems are often likened by nation-states to ‘taps’, which they think can be closed or opened through hydraulic interventions such as dams within their respective nation-states. The Brahmaputra river system has been the site of planned and ongoing mega-dams projects by China, India and Bhutan, all contributing to an intense geopolitical power projection in the river basin. Mega-dams on rivers systems are seen as important sovereignty markers; symbols of nation-state control over natural features. Highly dramatised terms such as ‘water wars’ are part of the geopolitical vocabulary and upstream hydropower dams are viewed as ‘water bombs’ by lower riparian nations, as in the case of the Medog dam project. China sits pretty at the top of Asia’s water tower, with complete control over Tibet’s rivers and significant material, technological and discursive capabilities to deploy unilateral hydropower development.

The Chinese hydrocracy has gone forward with mega-hydropower developments such as the Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze river and the Zangmu Dam on the Yarlung Zangbo, commissioned in 2015, with its top political leadership firmly backing these interventions as state symbols.

What are the risks for communities inhabiting the Brahmaputra river basin?

The communities living along the river system have adapted as the river has shaped and shifted over centuries. However, with interventions such as mega-hydropower dams by China, India and Bhutan, communities cannot use their traditional knowledge about the river system meaningfully, as the pace and occurrence of disasters have magnified. The upstream communities in Tibet as well as the downstream communities in India, Bhutan and Bangladesh have to live under the shadow of mega-hydropower dams with adverse consequences to their traditional lands and livelihood. The perennial flow of the Brahmaputra in downstream areas in India and Bangladesh depends on the flow of the Yarlung Zangbo. The blocking of that perennial flow, in order to maintain headwaters to operate a mega-hydropower dam of the magnitude that China is planning at the Great Bend, will have catastrophic consequences on surface water levels, and to overall monsoon patterns and groundwater systems of the river basin. This will affect downstream agrarian communities and the sensitive ecology of the overall Himalayan bioregion/ecoregion.

What explains the hydropower dam-building race in the Brahmaputra river basin?

There is a face-off between China and India on the Yarlung Zangbo-Brahmaputra river course. China has announced the biggest hydropower project at the Great Bend while India has announced its largest dam project, at Upper Siang. Bhutan has been planning and building several medium to small dams, which have raised concerns in downstream India and Bangladesh. None of the riparian countries of the Brahmaputra river basin have signed the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Non-navigational Uses of International Watercourses of 2014, and hence first user-rights on river systems are non-enforceable. China and India have an Expert Level Mechanism (ELM) since 2006, to discuss outstanding issues and share hydrological data, but do not have a comprehensive bilateral treaty to govern shared transboundary rivers. The outstanding land boundary dispute between China and India is weaved into the intense securitisation of the Brahmaputra river basin, which makes it an active site for strategic posturing by both countries.

A bioregional/ecoregional frame of protecting the Himalayas may help desecuritise Brahmaputra river basin.

What next?

A recent academic book by some Australian researchers titled Rivers of the Asian Highlands: from Deep Time to the Climate Crisis, puts forward important deep time (deep time means geological time; billions of years) perspectives to Himalayan river systems. The book juxtaposes a wider planetary thinking to emerge against the backdrop of narrow technocratic decision-making to build mega-dams within nation-states.

Tibet’s river systems are important to the Earth’s cryosphere, comprising permafrost and glaciers, and major climate systems directing climate and precipitation pathways such as the monsoon. Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs) have increased in the Himalayas with climate change events, exemplified by the Chungthang Dam collapse in Sikkim during October 2023, which caused widespread devastation to life and property to downstream communities. The dams across the Himalayas aim at territorialising river systems, breaking their natural life cycles. This affects agro-pastoral communities, biodiversity, living biota in rivers and wetland systems. The Brahmaputra river basin will turn into an active risk-scape if all these planned dams are built eventually.

An accurate sense of history will help contextualise the site of the Medog dam being built by China. One of the greatest earthquakes of modern times, the 1950 Medog Earthquake, or the Assam-Tibet Earthquake, which transformed the riparian landscape, had its epicenter at Medog in Tibet. The earthquake had disastrous effects downstream in Assam and Bangladesh, with the landscape until now trapped in an unending cycle of annual catastrophic floods.

Philip Ball in his book titled Water Kingdom: A Secret History of China describes the Yarlung Zangbo being viewed in Chinese history as a ‘river gone rogue’ as it turns sharply from its west to east route at the Great Bend, to turn south to enter India, with other major rivers in China running from west to east. While China is going ahead with building mega-dams in Tibet to correct this geographical anomaly by disciplining a ‘rogue river’, India can assume an important riparian leadership role for regional river systems by not mirroring what China does. A dam for a dam will make the entire Himalayan riparian/climatic systems run dry and turn it into a disaster-scape for its communities.

Mirza Zulfiqur Rahman is a Visiting Associate Fellow at the Institute of Chinese Studies, Delhi, India.

Published – January 06, 2025 08:30 am IST