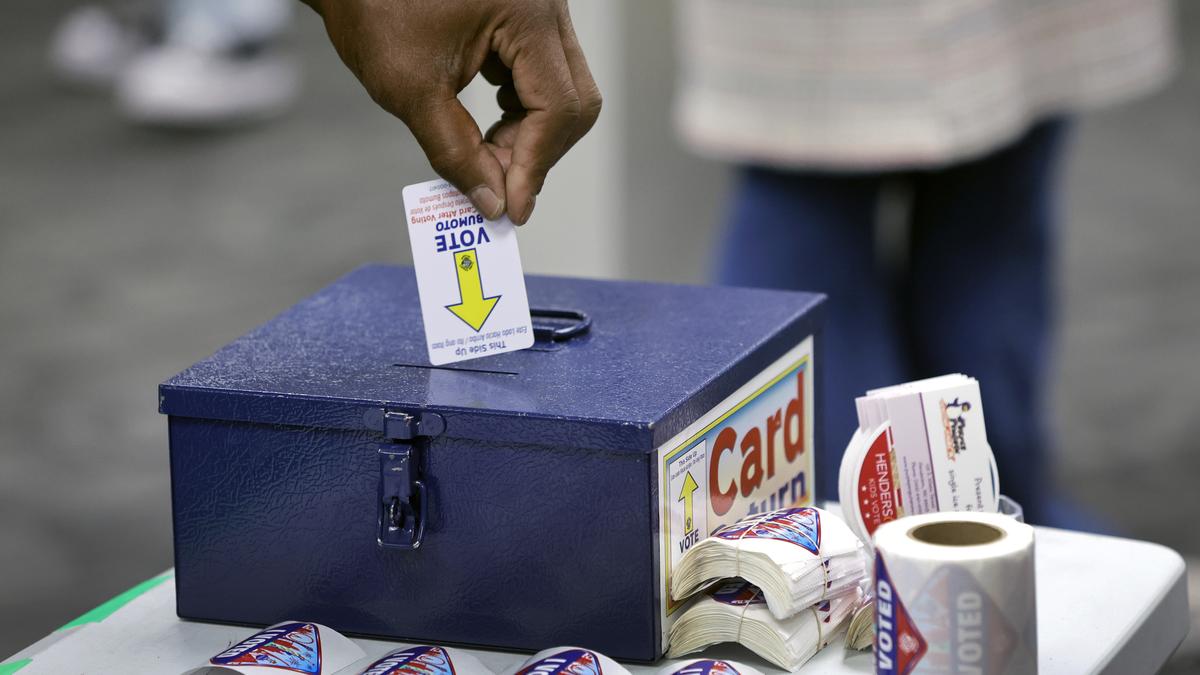

Donald Trump has returned to power in the United States following a decisive win in both the popular vote and electoral college vote in the presidential elections. This emphatic win made it easy for journalists to cover the results. It was clear fairly early during the counting process that Mr. Trump was going to win the election and also sweep the ‘swing States’.

This is in marked contrast to the 2020 election, which was full of controversies, both manufactured and real. A staggering number of Americans cast their ballots before voting day in that election, held during the COVID-19 pandemic; this stretched the counting process by days. Mr. Trump lost, but refused to concede the election to Joe Biden. The results were much closer than what the opinion polls had anticipated. The slow counting process strained the coverage.

In the U.S., on counting day, data is provided by the news agency, Associated Press (AP), and a few others. This means that the result is “called” by media outlets, which estimate the chances of a candidate winning a State based on trends that are available from this data. While the U.S. Federal Election Commission monitors implementation of campaign finance laws and the conduct of federal elections, it does not provide live electoral data. This is either collated by agencies such as AP, and released to subscribers via an Application Programming Interface, or is provided by each respective State, mostly by their Secretaries of State.

This is unlike the process in India, where the Election Commission of India (ECI) provides live counting data for each constituency, whether Assembly or parliamentary. Media outlets, especially television journalists, also use agencies or their own reporters to provide information on trends from counting centres. However, these are not always accurate. The slower and steadier trends that trickle in from the ECI website, which are authenticated by polling agents at counting centres, give media outlets and the general public a clear picture on electoral trends. The structured manner in which the ECI presents its results also helps media outlets and data enthusiasts, such as those in The Hindu, to parse that information and present it separately with more granular information. This includes, for instance, data on rural and urban voting trends across States.

While U.S. news agencies and media outlets are efficient in presenting results, the situation in India is different: the information is not available to only a select few outlets, and is collated and displayed in a structured manner by the ECI for anyone to use. The ECI also presents ‘deep-dive data’ — for instance, information from polling booths on how voters choose their candidates. It also provides Assembly segment-wise data for parliamentary constituencies. While this information is uploaded onto the website after a lag — it can take a few weeks after results are announced — the fact that it is made available is useful for social scientists and journalists to analyse the results even further, long after the excitement over elections dies down.

For a data journalist, the Indian model of providing electoral results via a public authority works much better than the American one. In recent years, the ECI has received a lot of flak for various issues, such as the robustness of the Electronic Voting Machines (an overblown controversy), the patchy implementation of the Model Code of Conduct (a legitimate criticism), the dilation of the voting process in some States (unavoidable in a few cases), and the relative laxity in regulating campaign expenditure (which is becoming a problem). But what must be appreciated by publicly minded people in India is that the ECI releases structured voting data in a transparent, timely, and efficient manner.

srinivasan.vr@thehindu.co.in

Published – November 15, 2024 01:44 am IST