The story so far: Sri Lanka’s presidential election will be held on September 21. Since it is the first time that citizens will have a chance to elect their leader after the unprecedented financial meltdown in 2022, their economic concerns are the chief poll issue. This marks a departure from the island nation’s last few elections that were dominated by promises of “eradicating terrorism” (the country’s three decade-long civil war ended in 2009), and pledges of delivering “good governance”, or “national security”. All main contenders running for president this time have promised to fix the country’s broken economy, offering mildly different versions of policy outlines tethered to an ongoing International Monetary Fund (IMF) programme.

What happened in 2022?

Sri Lanka’s classic twin deficit problem dramatically escalated when President Gotabaya Rajapaksa resorted to rash policy decisions, including significant tax cuts, an abrupt ban on chemical fertilizers, and a failure to devise a plan to meet debt repayment deadlines, especially after foreign reserves dwindled in the wake of the pandemic and questionable policy. In April 2022, Sri Lanka announced it would default on its foreign loans as the “last resort”. As the imports-reliant country ran out of dollars, essential supplies were severely hit. People were forced to contend with long queues for fuel and gas, shortage of food and medicines and prolonged power cuts. With no solution in sight, citizens took to the streets. The agitations soon grew into a formidable mass uprising and evicted Mr. Gotabaya from presidency. Soon after, President Ranil Wickremesinghe was elected to the country’s top office through a parliamentary vote.

When did the IMF step in?

Although the outgoing government of Mr. Gotabaya was considering seeking IMF assistance, it was only in March 2023 that the agreement for a $3-billion Extended Fund Facility (EFF) was finalised by his successor Mr. Wickremesinghe. The EFF sought to “restore Sri Lanka’s macroeconomic stability and debt sustainability, safeguard financial stability, and step up structural reforms to unlock the country’s growth potential”. Although Sri Lanka had obtained IMF assistance 16 times earlier, this was its first agreement after defaulting on its loans. The Fund underscored the need for a “comprehensive anti-corruption reform agenda”. In order to meet the targets set, the government undertook various policy measures.

It restored the taxes that were cut by the previous administration and increased the Value Added Tax (VAT) to 18% from January 2024. It went for market-pricing of fuel and energy, and agreed to “reform” state-owned enterprises, best known for their huge recurrent losses. Detractors read that as an alarm bell for a fire sale of strategic assets, but the government’s plans have yet to transform into actual deals. The Wickremesinghe government also passed at least 42 legislations for the country’s “economic transformation”.

What is the status of Sri Lanka’s debt?

In June this year, Sri Lanka sealed an agreement with the Official Creditor Committee (OCC), to restructure the debt owed to its bilateral lenders including India, and signed a separate agreement with China for debt treatment. The OCC is a platform comprising 17 countries including India and members of the Paris Club such as Japan, that Sri Lanka has borrowed from. It was formed in May 2023 to simplify Sri Lanka’s debt negotiations following its default. With the OCC, Sri Lanka reached a restructuring agreement for $5.8 billion of its bilateral loans.

Sri Lanka on September 19, 2024 said it reached agreements in principle to restructure approximately $14.2 billion of sovereign debt with the holders of its International Sovereign Bonds. On the domestic debt front, Sri Lanka’s effort at restructuring has sought to protect local banks, while transferring the burden to superannuation funds, including the Employees’ Provident Fund. The move, which diminishes the rate of return on investments and the final value of workers’ savings, drew huge flak and has been challenged in the Supreme Court.

Has the economy recovered?

Over the last year, authorities have been highlighting incremental gains towards macroeconomic stability.

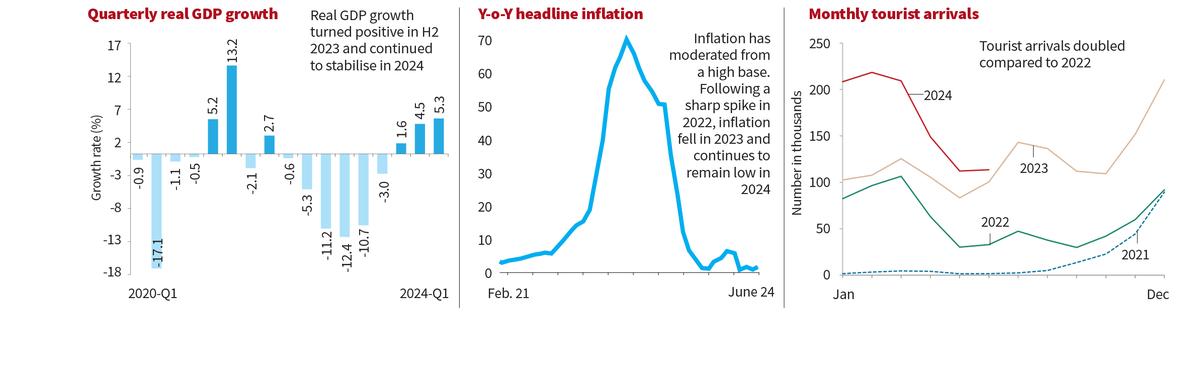

State revenue is up from 8% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the crisis year to 11%. The staggering 70% inflation seen in September 2022 dropped to 5.9% in February 2024. Sri Lanka’s economy is expected to grow around 2% to 3% this year, after the dramatic, near-8% contraction in 2022 and further contraction of 2.3 % in 2023.

The IMF has commended the government for its efforts and the government sees reason for promise. Foreign investment of around $1.5 billion made its way into Sri Lanka last year. The crucial tourism industry saw arrivals double, compared to 2022, and bring in revenue totalling over $2 billion. In the first half of 2024, Sri Lanka’s tourism revenue reached over $1.5 billion. Remittances from workers, mostly women engaged in domestic work in West Asian countries, showed an uptick of over 50%, amounting to nearly $6 billion in 2023. According to Central Bank data, Sri Lanka’s gross official reserves rose to $5.9 billion in August 2024. Export revenue from tea, rubber and spices increased, although the apparel and textile industry saw a drop in earnings. Flagging these macroeconomic gains President Ranil Wickremesinghe, who is among the key contenders this election, is running on the plank of economic “stability”.

How do people view the government’s claim of stability?

Some, especially from affluent sections, appreciate the President’s efforts towards economic recovery. However, a majority of Sri Lankans are reeling under the enduring impact of the crisis, and the austerity measures introduced as part of the IMF-led recovery programme.

The electricity tariff hike in 2023 threw over a million families off the grid, as they could not afford their bills, the Parliament was told in January. Sri Lanka has the highest electricity bills in the region, with consumers paying nearly three times more than their South Asian counterparts, according to local think tank PublicFinance.lk. Early this year, the energy regulator reduced the tariff by around 20%, but those who lost their connections last year are in no position to save enough to settle the outstanding arrears. There are no power outages in Sri Lanka now, but children studying in candlelight, women cooking with firewood, and refrigerators and fans falling silent in the scorching heat are not uncommon in poor households.

What about inflation?

The reduced rate of inflation is routinely cited by the Central Bank to signal respite, but it has not softened the blow for consumers. From the time food inflation soared to 94% at the height of the crisis, shoppers have been paying much more for essentials. According to the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, food inflation (Y-o-Y) accelerated marginally to 1.5% in July 2024 from 1.4% in June 2024. Further, non-food inflation (Y-o-Y) also accelerated to 2.8% in July 2024 from 1.8% in June 2024. Inflation continued to remain below the targeted level of 5% even after this acceleration, it noted, implying that compared to its rocketing in 2022, the rate of price increase has slowed down.

Meanwhile, higher utility bills, mainly electricity and water, cooking gas and transport costs, have only further drained the stagnant incomes of families. Add to this the 18% VAT. While some essentials, including wheat flour, baby food, and medicines are VAT-exempt, everything, from a cup of tea at the roadside shop to a lunch packet, costs three or four times as much as it did before 2022. The increased cost of producing, sourcing, and supplying items in Sri Lanka’s food ecosystem travels fast to the consumer.

What is the impact on people?

While official numbers appear to scream relative macroeconomic stability, people struggle silently to put food on the table every day. Sri Lanka is recovering, but not for all. During the crushing economic crisis, at least half a million jobs were lost, food insecurity and malnutrition became widespread, poverty doubled, and inequality widened, according to the World Bank. Scores of small and medium-sized enterprises plunged into losses and are struggling to bounce back. A UNDP report published in March 2024 said approximately six in 10 (or 55.7%) of all people are multi-dimensionally vulnerable in at least three of the 12 weighted indicators of access to health, education, employment, and income.

Further, 54.9% of households in Sri Lanka are indebted, and 60.5 % of households are grappling with a drop in household income after the crisis, estimates the Department of Census and Statistics. The poor are consuming less, spending a lot more for a lot less, and increasingly, borrowing to make ends meet. The survey showed 91% of households reporting an increase in their total household average monthly expenditure. That too when real wages and incomes have fallen after the pandemic, and job losses exceed one million in the construction sector alone.

Sri Lanka’s election will see stability and suffering clash at the ballot box.

Published – September 20, 2024 08:30 am IST