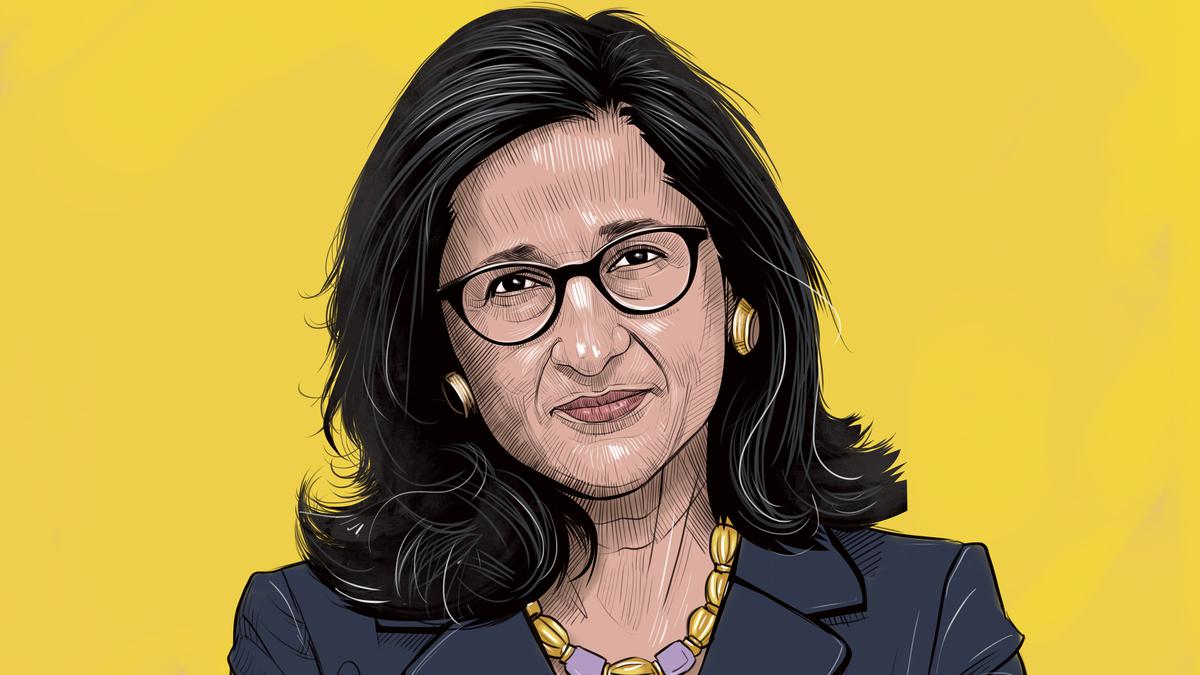

On April 17, students at Columbia University escalated their ongoing protests against the war on Gaza by occupying university lawns and creating a ‘Gaza solidarity encampment’. At about the same time, Columbia University’s first woman president Nemat ‘Minouche’ Shafik was attending a Congressional hearing before the U.S. House Committee on Education and the Workforce wherein she testified about the University’s action-plan to counter “anti-Semitic” instances on the campus. In a gruelling interrogation, Ms. Shafik was asked whether phrases such as ‘from the river to the sea, Palestine will be free’ or ‘long live intifada’ were anti-Semitic. She said that while to her it seemed anti-Semitic, to others it did not.

“Trying to reconcile the free speech rights of those who want to protest and the rights of Jewish students to be in an environment free of discrimination and harassment has been the central challenge on our campus and numerous others across the country,” Ms. Shafik told the committee. Amid calls for her resignation as president, she assured the committee that the university will continue to be a safe space for Jewish students and that students violating university policy would face consequences. And the very next day, Ms. Shafik asked the New York Police Department to enter the campus and arrest the students who were peacefully protesting in the encampment. More than 100 students were arrested.

Also read: Why are students protesting across U.S. campuses? | Explained

The Baroness

Ms. Shafik’s career has been a journey of many milestones. She was born in Alexandria, Egypt, and when she was four years old, her family moved to the U.S. in the mid-1960s. After doing her masters from the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and her DPhil from Oxford, she went on to work for the World Bank. At age 36, she became the youngest Vice President of the World Bank. Her work mostly focussed on global development and foreign aid programmes. She also worked with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Department for International Development of the U.K. In 2014, Ms. Shavik joined the Bank of England as its first Deputy Governor on Markets and Banking, wherein she worked on the contingency planning around the Brexit referendum. She is a member of the U.K. House of Lords and her full title is ‘The Baroness Shafik DBE’.

“I have had jobs that are about doing good, such as fighting poverty or leading educational institutions as well as jobs that are about preventing bad things from happening, like at the IMF and Bank of England,” Ms. Shafik has said of her career. “Both are vital if we are to make and secure progress for humanity.”Columbia wasn’t Ms. Shafik’s first university presidency. In 2017, she took charge as the president of LSE, her alma mater. Even though Columbia seems to be her hardest stint yet, her tenure at LSE was not very smooth either.

It was during her time as president that higher education in the U.K. faced a massive crisis, wherein university staff across the U.K. represented by the University and College Union (UCU) went on successive strikes, from 2018 to 2023, against pension cuts, pay decline, pay inequality, and exploitative and insecure contracts, despite mounting workload. At the time university administrators, including Ms. Shafik, came under intense criticism for not doing more on the national stage for striking faculty. In an interview to The Beaver, the LSE’s student newspaper, UCU President Janet Farrar said university directors are “on the most ridiculous salaries that you’ve ever heard”, quoting Ms. Shafik’s pay in 2019-20, which amounted to a whopping £5,07,000. There are staff members “who are highly casualised, who are using food banks, who are burning out with stress, who are experiencing race, disability, and gender pay gaps for work of equal value,” Ms. Farrar said.

Interestingly, Baroness Shafik in her latest book in 2021, What We Owe Each Other: A New Social Contract, talks about the need for a new social contract for society in order to resolve the increasing anger manifested in polarised politics, culture wars and conflicts over inequality and race. In the book, she calls upon individuals and institutions to rethink how they can better support each other so that society can prosper. As tensions across campuses peak in the U.S., maybe it’s time Ms. Shavik revisits her own position within society and takes her own advice.