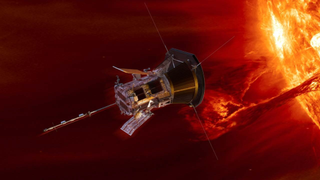

On Christmas Eve (Dec. 24), a NASA spacecraft made history by coming closer to the sun than any spacecraft ever has before.

This record-breaking feat was conducted by the Parker Solar Probe, which flew to within 3.8 million miles (6.1 million kilometers) of the sun, braving the blistering heat of our star’s outer atmosphere, the corona.

The flyby, which should have occurred at 6:53 a.m. EST (1153 GMT), was the 22nd time Parker had made a close passage to the sun. Though the NASA craft is expected to make at least two more flybys of the sun, this is the closest it has ever and will ever come to the star. And, to be clear, we say “should have” because NASA had to lose contact with the spacecraft during this flyby; the first proof that Parker survived will arrive on Dec. 27, according to the agency.

Parker is no stranger to smashing records. On Sept. 21, 2023, Parker hit a speed of 394,736 miles per hour (635,266 kilometers per hour) to cement its record as the fastest object ever built by humanity.

During its Christmas Eve passage, scientists say the sun-touching spacecraft would have been traveling at 430,000 mph (692,000 kph), also breaking its previously set speed record. For comparison, that is around 300 times faster than the top speed of a Lockheed Martin jet fighter here on Earth.

This incredible feat of speed could be reached thanks to the aid of seven gravity “boosts” from Venus flybys, the last of which occurred in November 2024.

The Parker Solar Probe continues its true mission

But breaking records is just a byproduct of Parker’s main mission: to learn more about the sun. In particular, the spacecraft needed to brave the 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit (980 degrees Celsius) temperatures it will experience to collect data about the solar corona.

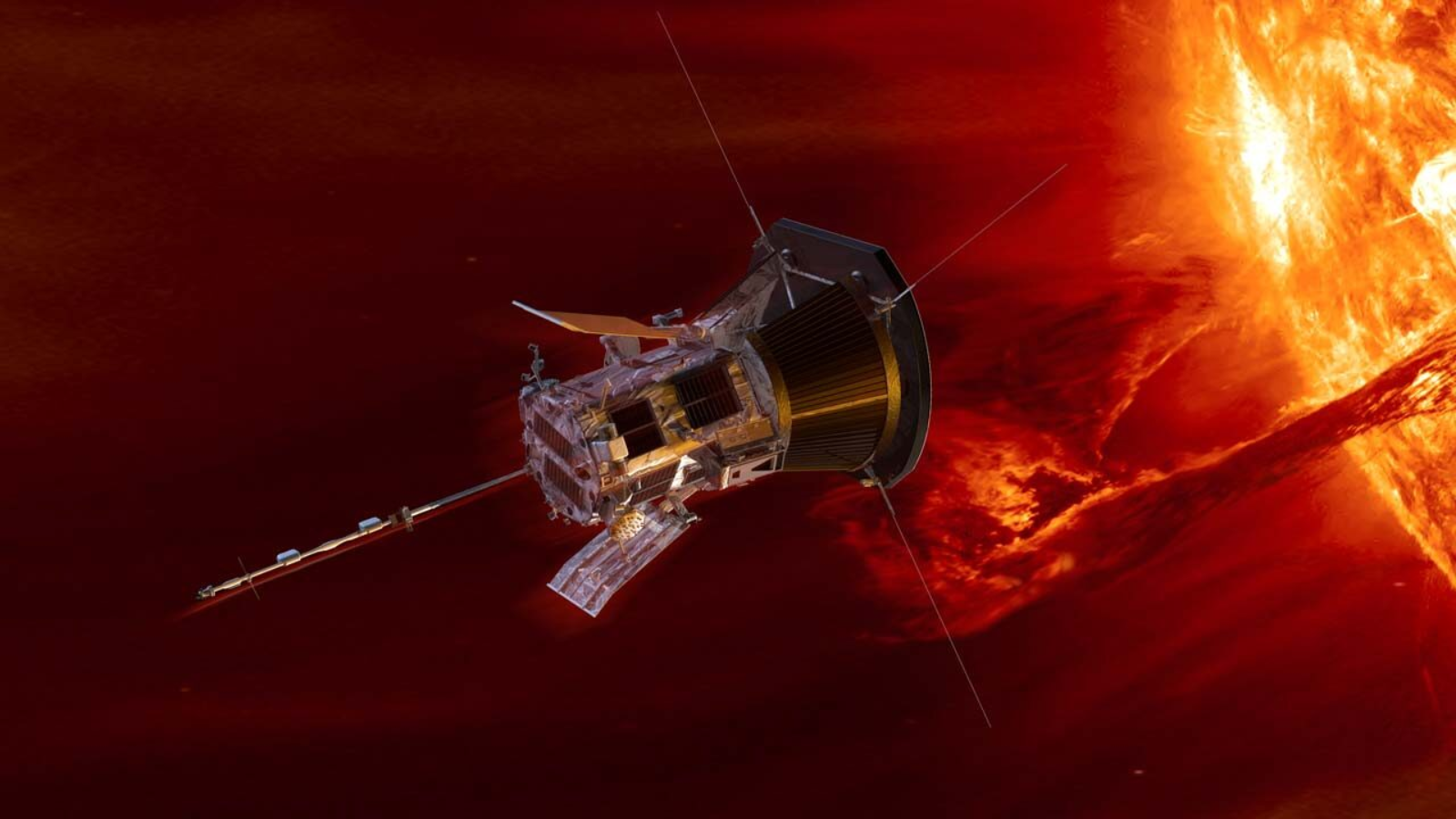

Scientists hope this data can help solve a long-standing mystery about the sun’s outer atmosphere, which has troubled them for decades. The so-called “coronal heating problem” refers to the fact that, despite being further from the sun’s primary source of energy (its core), the corona is much hotter than the sun’s surface, the photosphere.

Our standard model of stars suggests that the closer one gets to the stellar core, where main sequence stars like the sun perform nuclear fusion to forge hydrogen into helium and release energy, the hotter it gets.

All the layers of the sun seem to stringently obey this rule — except the corona, which can reach temperatures in excess of 2 million degrees Fahrenheit (1.1 million degrees Celsius). Around 1,000 miles closer to the source of the sun’s heat, the photosphere reaches a relatively balmy 7,400 degrees Fahrenheit (4,100 degrees Celsius). That’s like finding out this Christmas that your chestnuts only roast when you drive them a mile away from an open fire!

Therefore, there must be an extra mechanism heating the solar corona, and scientists are understandably eager to discover what it is.

Parker will continue its mission, making flybys of the sun on March 22, 2025, and then its final planned flyby will happen on June 19, 2025.

During both of these approaches, the spacecraft will come almost as close to the sun as it did on Christmas Eve while traveling at a similar speed.