NATIONAL HARBOR, Md. — When a boy named Elliott found an alien in the classic 1982 film “E.T.” it offered easy answer to the question on every astronomer’s mind: Are we alone in the universe? In reality, however, scientists have yet to solve that query.

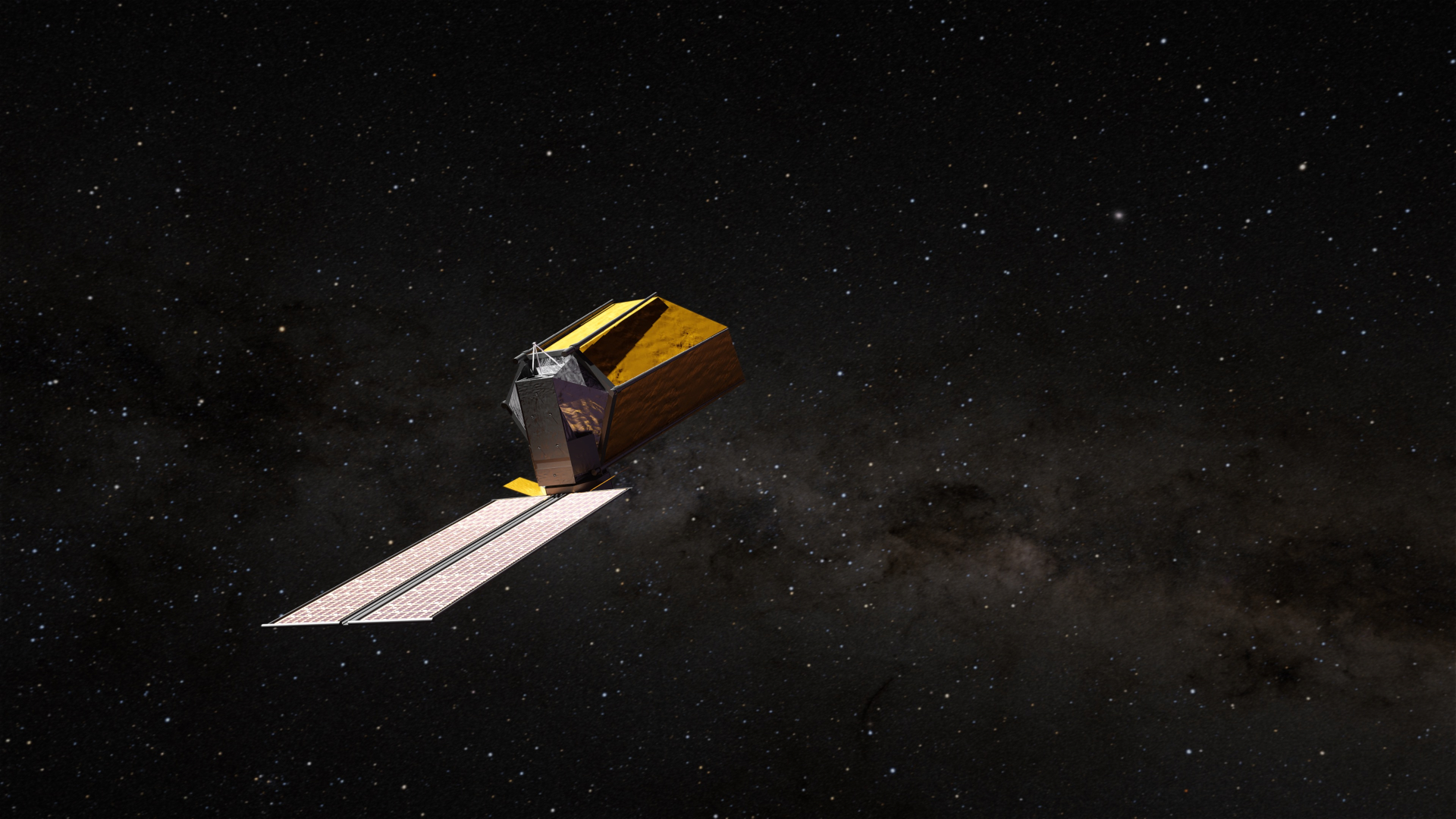

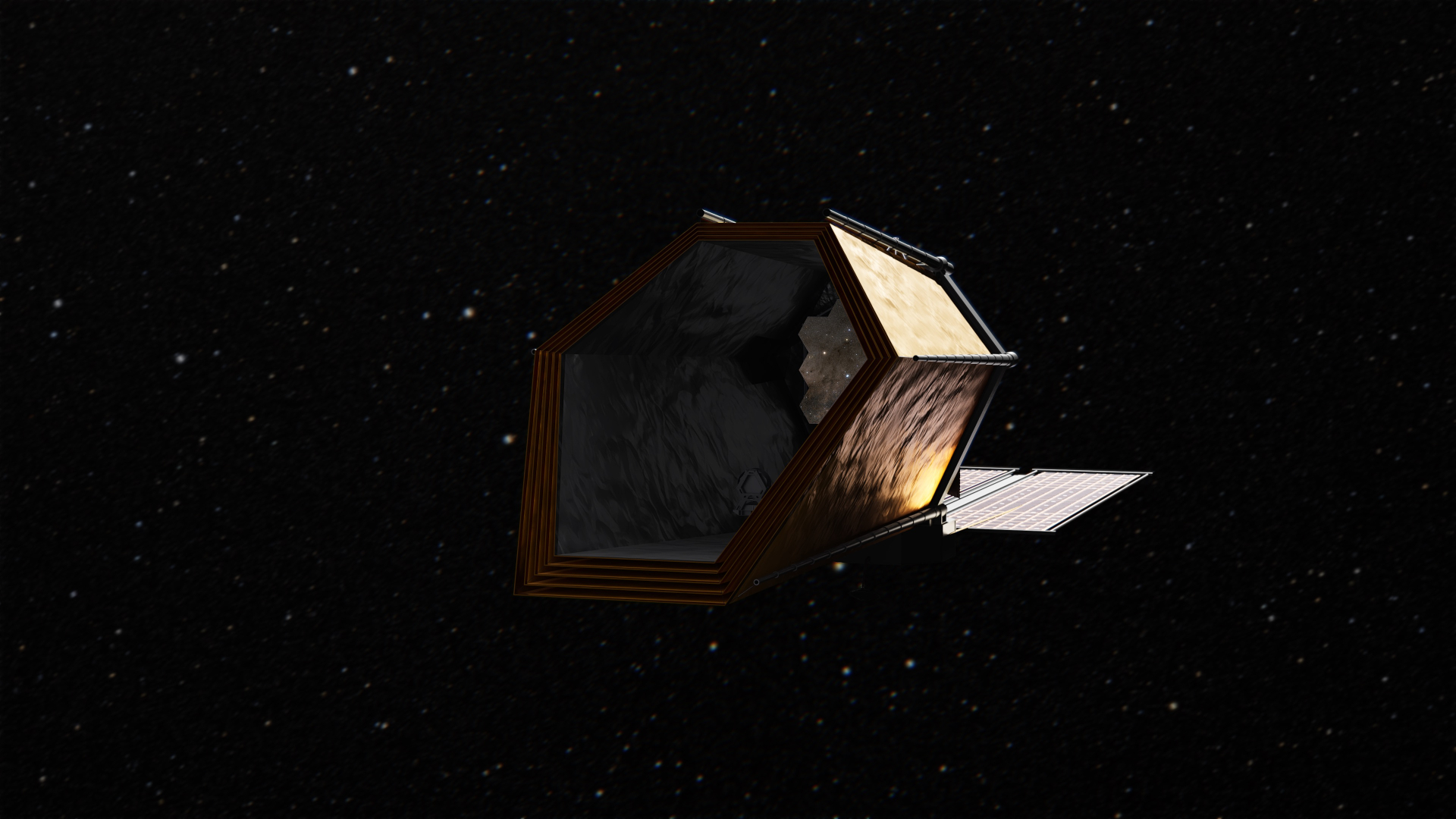

That could soon change, thanks to a new NASA flagship telescope being designed to seek out strange new worlds that could support life as we know it. Called the Habitable Worlds Observatory, the telescope is so massive it may even need to ride a next-gen megarocket like SpaceX’s Starship to reach space; it will also require new technological innovations to hunt for Earth’s twin across the light-years. Yet, even with such hefty demands, this project was tapped as a top priority for NASA in the Decadal Survey on Astronomy and Astrophysics 2020 (Astro2020), an influential report that aims to set a roadmap for the astronomy community within the decade following its release.

“The question ‘Are we alone?’ is one of the most significant questions, not just in the history of science, but in the history of humanity, and we are at the precipice of actually having the tools and technologies that are required to tackle this question in a rigorous and scientific fashion,” Giada Arney, the interim project scientist for the Habitable Worlds Observatory, told a crowd of scientists during a plenary talk here at the 245th American Astronomical Society meeting on Wednesday (Jan. 15). “We might learn the answer to this question within our lifetimes, and the answer to that question is a discovery, the implications of which would ripple through future millennia.”

Arney, a planetary scientist based at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, is working with a vast team of scientists to develop the Habitable Worlds Observatory into a powerful tool for astrophysics research and exoplanet discovery. Last summer, NASA opened a new program office at Goddard for the space telescope and announced it has earned $17.5 million in funding to explore some of the key technologies needed to bring the instrument to fruition. Now, the team is gearing up for a major science conference in late July to outline the science the Habitable Worlds Observatory could do.

“We’re very early in the design phase of HWO,” Arney said, using NASA’s shorthand for the observatory. “We’re still iterating through a number of design concepts, so we don’t know exactly how HWO is going to look when it launches.”

One thing is for sure, though: It’s going to be big.

Lee Feinberg, HWO’s principal architect based at Goddard, said in a separate presentation that NASA is currently envisioning a massive space telescope nearly 20 feet (6 meters) wide, and suggested it could get as large as 26 feet (8 m). The Hubble Space Telescope, for comparison, has a 6.5-foot (2 m) aperture, he said.

Even the smallest version of HWO will need a huge rocket to haul it into space. Blue Origin’s New Glenn rocket, which has a huge 23-foot (7 m) fairing, could fit the bill, Feinberg said.

“It would be really challenging to fit in that rocket from a mass perspective, but these are the kind of details that we’re trying to understand,” Feinberg said.

For larger versions of HWO, SpaceX’s massive Starship — currently the world’s tallest and most powerful rocket, with a nearly 30-foot (9 m) payload bay, is an option not just for launching the rocket, but also as a way to return to the observatory in space for periodic servicing, just as NASA space shuttle astronauts did with Hubble, according to early designs.

The space telescope will have four primary instruments, including a super-sensitive coronagraph that can detect Earth-size planets around distant stars. A prototype of its coronagraph should launch into orbit in 2026 on NASA’s new Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope. Current HWO designs call for the coronagraph, a high-resolution imager, an advanced spectroscope and a fourth instrument yet to be determined.

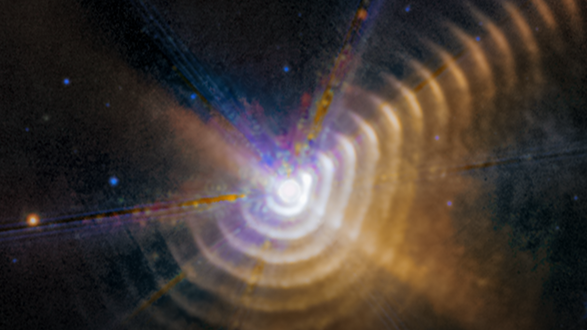

The current plan for HWO is to launch the observatory sometime between 2030 and 2040 to catalog at least 25 Earth-like exoplanet candidates for biosignatures, or signs that life that could be present on those worlds. The oxygen, methane and ozone of modern Earth are examples of possible biosignatures, Arney said.

If HWO successfully finds those signs of life, it would be a watershed moment for humanity’s understanding of how common life might be in the universe. The reverse, however, is also possible. If HWO samples 25 exo-Earth candidates and comes up empty, that could be seen as the first “upper-limit” on the frequency of life beyond Earth, Arney said.

“HWO will either tell us we are not alone, if there are bio signatures that can be observed on an exo-Earth candidate orbiting a nearby star, or it will tell us for the very first time just how alone we are,” she said. “Either answer would be profound, and either answer would change the way we see ourselves in relation to the rest of the universe.”