Former U.S. President Jimmy Carter had an intense relationship with India, both at a personal level and over the original “Indo-U.S. nuclear deal” for the Tarapur Atomic Power Station that even threatened to derail his mega visit to India in 1978. In a statement on Monday, Prime Minister Narendra Modi lauded Mr. Carter’s efforts for “global peace and harmony” and said that his “contributions to fostering strong India-U.S. ties leave a lasting legacy”.

Mr. Carter’s two-day visit to India (January 1-3, 1978) was billed a major moment in bilateral ties. Mr. Carter and First Lady Rosalynn Carter had embarked on a five-nation tour to Poland, Iran, India, France and Belgium, arriving in New Delhi from Tehran where the Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi had thrown a New Year’s eve banquet for them.

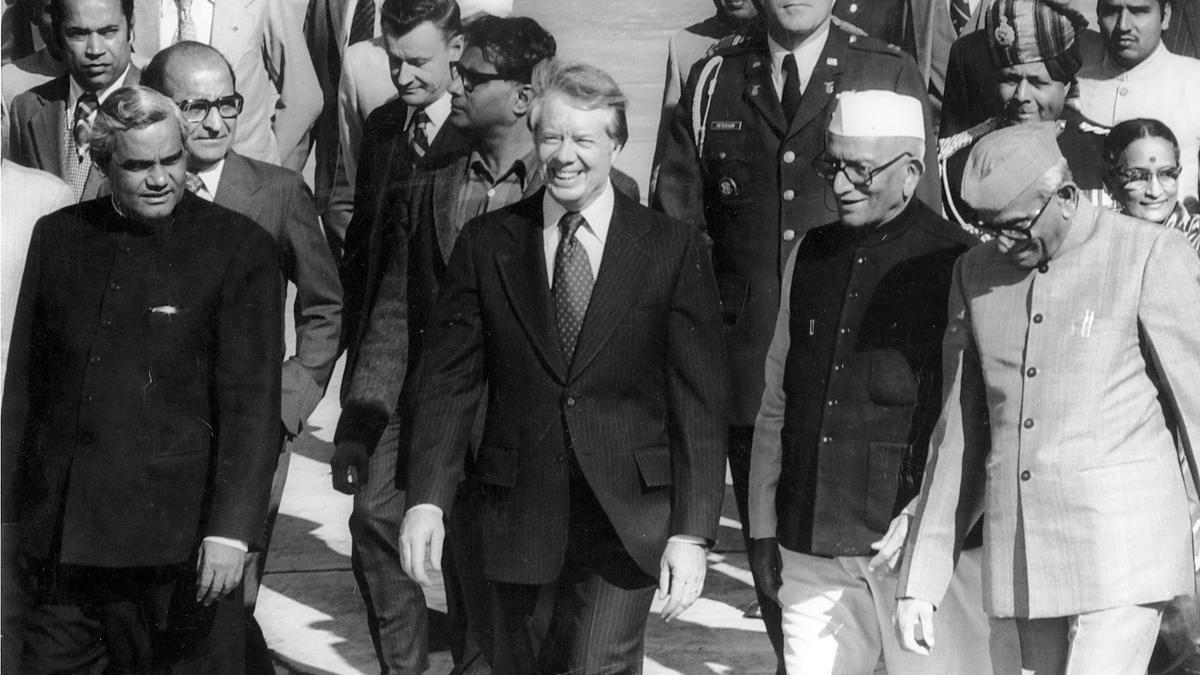

The visit was also significant, as unlike his predecessors, Mr. Carter hadn’t combined it with a visit to Pakistan. The Carters were received not only by Prime Minister Morarji Desai and the members of the Cabinet, but by President Neelam Sanjiva Reddy himself, a rare gesture. Welcoming him at the airport, Mr. Reddy called Mr. Carter a “great humanist”, and referred to Mr. Carter’s mother Lillian Carter’s “selfless service” in Maharashtra as a member of the U.S. Peace Corps in the 1960s.

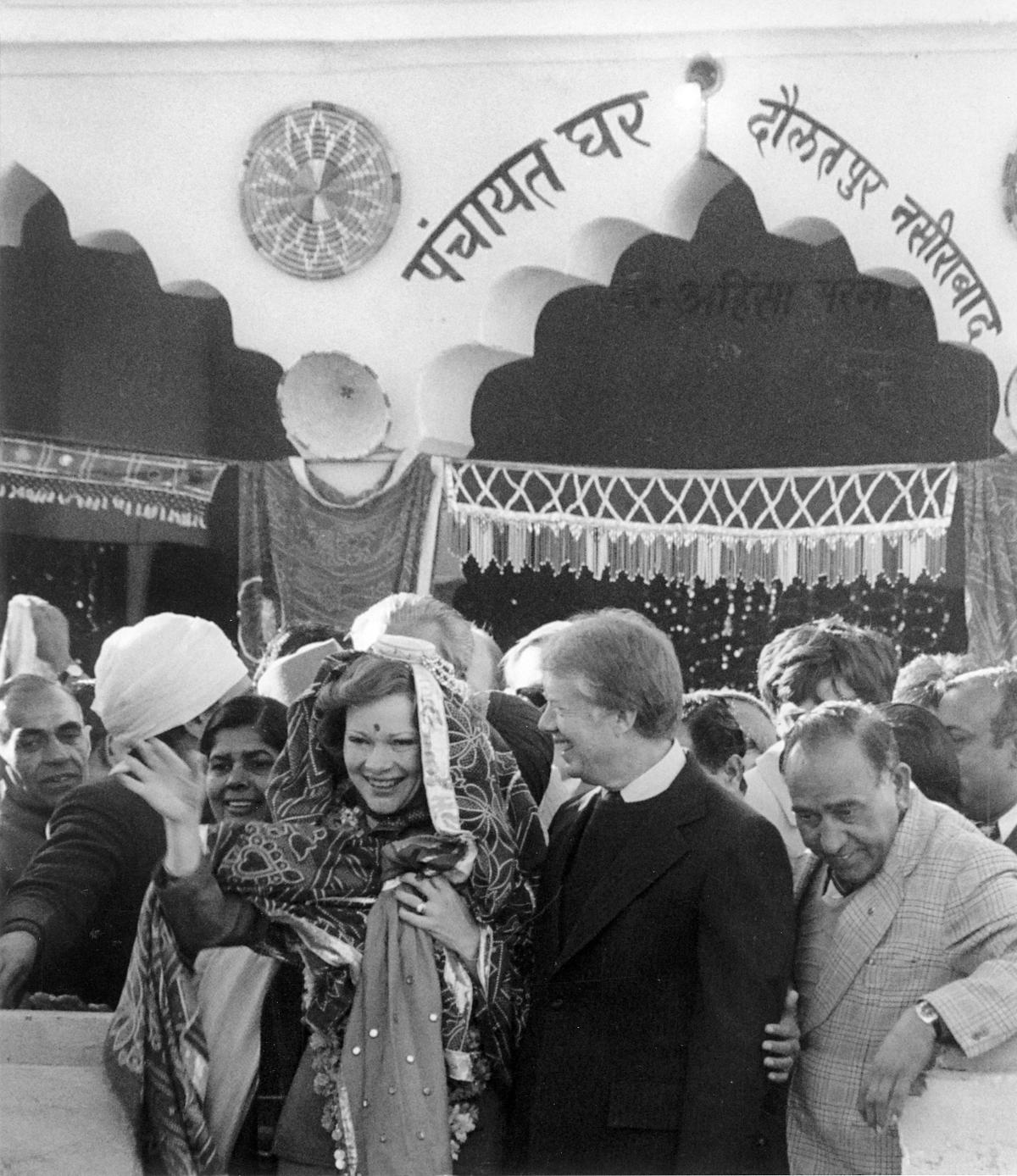

Rosalynn Carter wears a shawl presented to her by the villagers in Daulatpur Nasirabad, India, as President Carter smiles approvingly. The spot of red dye on the forehead, a tilak, is a Hindu mark of respect and friendship. The name of the village was permanently changed to Carterpuri in honour of their visit. | Photo Credit: U.S. Embassy Delhi/ flickr.com

Mr. Carter, clearly delighted by the reference, the reception and the crowds who lined the streets, attended a public rally with Mr. Desai at the Ramlila Maidan. He said the connection with India was a deeply personal one because of his mother’s love for “this nation and its people”. In Parliament, he received a standing ovation as he drew parallels between the fight for democracy in India against the Emergency that had ended two years before, and the U.S. protests against the Watergate Scandal that had ousted his predecessor Richard Nixon.

However, the bonhomie during the visit was dimmed somewhat by U.S. expectations of the Indian government at the time. Ahead of his arrival, Mr. Carter had said in an interview, “We go to India, the biggest democracy in the world, one that in recent years has turned perhaps excessively toward the Soviet Union but under the leadership of Prime Minister Desai is moving back towards the U.S. and assuming a good role of, I would say, neutrality.” His statement had left some feathers ruffled.

Non-Proliferation Treaty

It was also clear that during talks with Mr. Desai, Mr. Carter intended to nudge India towards the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), given the U.S. anger over India’s nuclear tests in 1974, and to use India’s requirement for nuclear fuel at the Tarapur Atomic Power Station as leverage. Morarji Desai, an avowed Gandhian who was against the atomic bomb, nonetheless refused to budge on nuclear sovereignty issues. In a “hot mic” moment during a recess in talks between the two leaders, Mr. Carter inadvertently spoke to U.S. Secretary of State Cyrus Vance near television microphones that broadcast him speaking of disagreements during the negotiations, and referring to Mr. Desai as “pretty adamant” on the nuclear issue, The Hindu reported at the time.

“While the U.S. Presidential outreach was well-meant, it was clear that on the nuclear issue there remained a substantial gap between what the U.S. wanted India to do on non-proliferation, and the safeguards India was willing to submit to,” said former Ambassador to Russia and disarmament expert at the Ministry of External Affairs Venkatesh Verma, explaining that the underlying question was about “India’s place in the larger nuclear order of which the U.S. was the primary custodian”.

Both sides brushed aside the comments, but it was clear that the talks on the nuclear issue were unsuccessful amidst a visit otherwise quite productive on issues like space cooperation and agricultural assistance. Summarising the visit, then-U.S. Ambassador Robert Goheen wrote in a cable dated January 5, 1978 that the “determination of Prime Minister Desai and his colleagues not to allow the disclosure of the President’s conversation with the Secretary on the nuclear question to sour the atmosphere is a testimonial to the goodwill that prevailed,” but acknowledged that Indian newspaper commentary had focused on “differences in the nuclear field”. As he left, Mr. Carter hoped his visit would be a “turning point” in the India-U.S. relationship, but that hope was not fulfilled. Ties between the U.S. and India continued to struggle over several issues like U.S. support to Pakistan, the Cold War, and nuclear negotiations, and the next U.S. Presidential visit to India, by Bill Clinton, took place more than 22 years later.

It took India and the U.S. another three decades to forge an agreement on nuclear issues, with the Indo-U.S. civilian nuclear deal forged between Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and U.S. President George Bush. By coincidence, as the deal was being finalised in 2006, Mr. Carter returned to India and met with Mr. Singh. Both leaders, known for a softer style of diplomacy, died within a few days of each other.

Published – December 30, 2024 10:33 pm IST