When Anura Kumara Dissanayake was elected President of Sri Lanka in September, and his National People’s Power [NPP] alliance swept the general elections on November 14, most international news headlines stamped the winners as ‘Marxist’.

The tag was hardly positive or even neutral with its connotations of wild-eyed radicalism. The insinuation was that Sri Lanka’s ongoing programme with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) would derail, and economic stability and recovery would be disrupted.

President Dissanayake, through his November 21 policy statement to the new Parliament, that he will take forward the IMF framework and the aligned debt treatment plans — finalised by his predecessor — tried to allay these fears.

President Dissanayake, through his November 21 policy statement to the new Parliament, that the IMF framework and the aligned debt treatment plans with bilateral and private creditors — finalised by his predecessor — will go ahead, tried to allay these fears.

So where does this ‘Marxist label’ on Sri Lanka’s new government come from? The NPP is an eclectic social coalition of some 21 groups, including political parties, youth and women’s organisations, trade unions and civil society networks. But one political party forms its political, if not ideological, core — the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP or People’s Liberation Front).

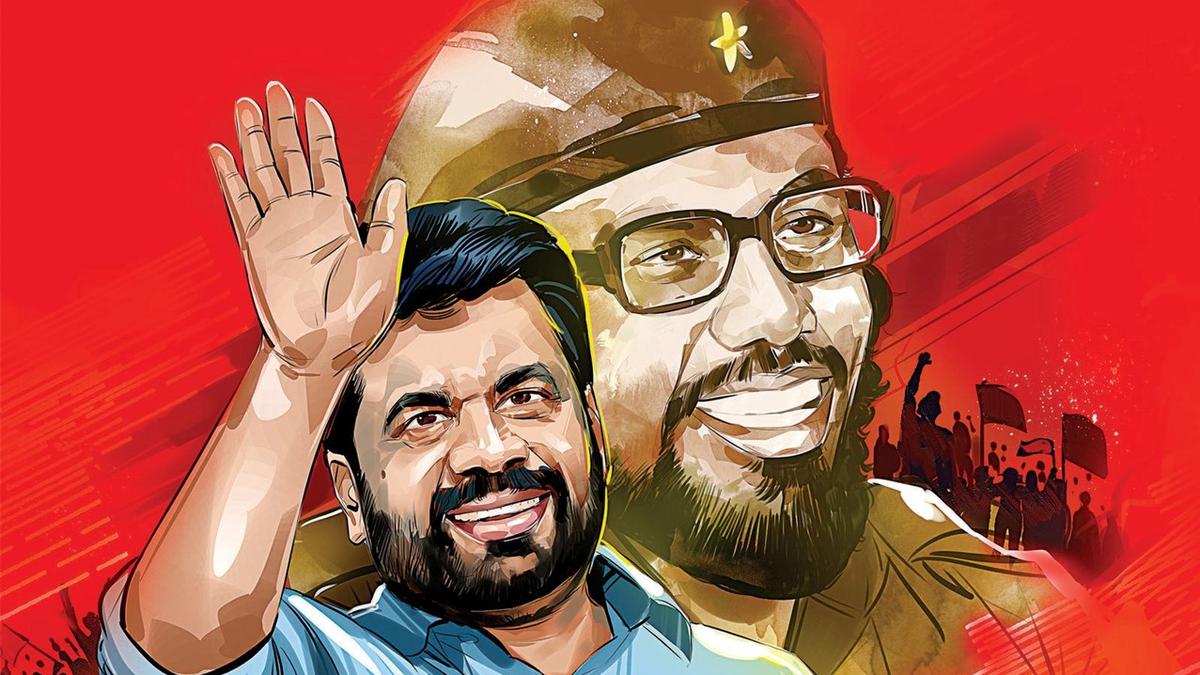

In fact, it was JVP leader Mr. Dissanayake who created the NPP in 2019 to widen the party’s appeal beyond its traditional cadre base and boost its chances at the polls. His political enterprise, which has now secured a massive victory, has turned a new page in post-colonial Sri Lanka, where politics has been dominated by just two parties and their offshoots, and the five elite families controlling them.

The JVP’s office in Battaramulla, a suburb about 10 km east of Colombo, is located close to parliament, although the party has rarely been close to power in the six decades of its existence. Three large black-and-white portraits of Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and Vladimir Lenin adorn the white wall of the main meeting room. Party cadre, regardless of position or prominence, make and serve tea to their guests. Above the reception desk at the entrance is a photograph of the party’s founder and charismatic leader Rohana Wijeweera, an infallible icon for its cadre. His mane, cap, and beard suggest Che Guevara-inspired self-styling.

Wijeweera began what became the JVP in 1965, exactly three decades after Ceylon’s left movement birthed the country’s oldest party, the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), consequent to serial fractures within the Left. The LSSP split during the Second World War, leading to the formation of a pro-Moscow Communist Party. The cracks within the CP in the 1960s, triggered by the Sino-Soviet dispute, and internal tensions over the parliamentary road to socialism would, in turn, lead to the formation of the JVP, as a revolutionary party with Marxist-Leninist orientation.

‘Five classes’

Attracted to Maoism in his student days in the Soviet Union, Wijeweera joined the Communist Party (Peking wing – CP) of Sri Lanka in 1964, and became a youth leader. He challenged the party’s leadership, on their interpretation of class politics and revolution, and was subsequently expelled in 1965. His independent faction morphed into the JVP. Wijeweera and his comrades held political lessons for rural Sinhala youth, called the “Five Classes” that analysed Sri Lanka’s social and political order; Indian hegemony; the reformist left and coalition politics; and the parliamentary road to socialism. As part of preparation to achieving their objective of seizing state power, they trained in the use of shotguns and put together explosive devices.

The story of the JVP’s rise in the late 1960s and fall in the next two decades unravels in the backdrop of two major changes in Sri Lanka — President J.R. Jayewardene’s open economic reform in 1977 and the beginning of a full-blown civil war after the 1983, state-sponsored anti-Tamil pogrom that he falsely attributed to Left parties, including the JVP.

The gist

The Lanka Sama Samaja Party, Sri Lanka’s oldest party, split during the Second World War, leading to the formation of a pro-Moscow Communist Party

The cracks within the Communist Party in the 1960s, triggered by the Sino-Soviet dispute, and internal tensions over the parliamentary road to socialism would, in turn, lead to the formation of the JVP

The party led two insurrections against the state — in 1971 and in 1987-89 — which triggered massive state reprisal. After a few years of underground existence, the surviving cadre resurrected the party

The JVP’s first insurrection in 1971 came out of frustration that the left-wing Sirimavo Bandaranaike-led government was not doing enough to meet the aspirations of educated but unemployed young people, and in changing the social, economic and political order inherited from the British. The discourse was anti-imperialist and socialist. The insurgents attacked dozens of police stations, to capture weapons and ammunition.

The second insurrection, from 1987 to 1989, roughly coincided with the party’s embrace of Sinhala-nationalism; its fierce opposition to Tamil self-determination; and to the signing of the India-brokered 1987 Accord aimed at ending the war, with boots-on-the-ground in the form of the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF). To Tamils in the far north of the island, the JVP appeared as Sinhala chauvinist instead of progressive, although the party never directly engaged in anti-Tamil violence.

In both insurrections, where the JVP took up arms against the state, its representatives, supporters, and dissidents from the Left [in the second insurrection], the state’s counter-insurgency response was many times more lethal, resulting in the death and disappearance of tens of thousands of Sinhala youth. Wijeweera himself was executed while in state custody in 1989.

Somawansa Amarasinghe, the only politburo member to survive the repression of the 1980s, escaped to India and subsequently to Europe. After a few years of underground existence, the surviving cadre resurrected the party, even as the country was increasingly preoccupied with massive human rights violations in the south and the raging war in the north-east. The JVP tentatively contested in the 1994 general election through another party, winning one seat. Within the next few years, the JVP warmed up to the political mainstream, winning more seats in parliament between 2000 and 2004, and four Cabinet-level ministerial portfolios in 2004–05, in a short-lived coalition with the Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga government.

Two splits

The new course of the JVP is defined by two consequential splits, linked to the party’s proximity to Mahinda Rajapaksa who began dominating the political scene from the early 2000s. They were also fuelled by internal differences on the dilution of leftism for “patriotism” (Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism), versus emphasis on Wijeweera’s socialist ideology and the party distancing itself from Mr. Rajapaksa and his pro-war stance.

Since the breakdown of the 2001-03 ceasefire, the JVP unambiguously backed Mr. Rajapaksa’s hawkishness in delivering a political solution to the Tamil question, and the military defeat of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), with scant regard to Tamil lives. The JVP’s differences with Rajapaksa were more to do with their unease over ‘family-rule’ and his socio-economic policies rather than his militaristic response. However, its parliamentary group leader and reactionary politician Wimal Weerawansa disagreed, and broke away with a quarter of its legislators, forming the Jathika Nidahas Peramuna or National Freedom Front in 2008, that until recently firmly planted itself in the Rajapaksa camp. Four years later a Marxist faction within the residual JVP also split from it, criticising the party’s unconditional support to the Rajapaksa regime on the handling of the war, and its complete surrender to electoral politics. This group led by Kumar Gunaratnam formed the Frontline Socialist Party in 2012, the chief critic of the JVP today, from the left.

In 2014, Mr. Dissanayake was named leader of a party that had to stabilise itself, after shedding both its racist right-wing and its dissenting left-wing. The splits allowed the JVP to refashion itself, blurring its past profiles, and making a reputation for itself inside and outside parliament, as a bold critic of corruption and nepotism, and as an upholder of the rule of law and liberal democratic norms. The party, till date, is wary of clearly defining its position on the unresolved ethnic question. It also evades the language of class politics. In an interview to The Hindu in December 2023, Mr. Dissanayake said: “Labels have always given wrong perceptions. Left politics is not a bad thing, it is a good thing. Some people demonise this. That is why we say we are focussed more on working for the majority of our people, rather than on labels.”

Published – November 24, 2024 04:00 am IST