Growing up I always wondered why we commemorate historical events on a yearly basis, like Independence Day or Gandhi’s birthday. While formal education failed to develop that understanding, reading gave me a perspective on the power history and why we need to keep learning from the past to avoid repeating mistakes of the past. In his latest book, Who is Equal?, senior advocate and queer rights activist Saurabh Kirpal has tried to do the same by drawing inspiration from history on how we fared on the ideals of equality and why it remains a quest worth fighting for. Edited excerpts from an interview.

In India’s 78th year of Independence, do you think talking about equality is still relevant?

Certainly, talking about equality would become irrelevant when there will be no inequality. Only a person completely removed from the reality of India would say that there is no inequality. Forms have changed, the ways you discriminate have changed, but sadly the axes around which inequality exists has been persistently stubborn, which I talk about in my book in terms of religion, caste and gender. They’re the same grounds on which discrimination happened in 1947 as it does now.

After judgments like the NALSA and Section 377, some people strongly believe that equality is here. Do you believe that’s the case?

I think privilege gives you a cushion not to be able to see discrimination on a daily basis. The removal of the tag of criminality under Section 377 only happened in 2018, not when we became independent. Equally, when the Constitution declares that everyone is equal under Article 14 or in certain directive principles, it’s delusional to think that these magic words will lead to equality descending upon the polity as a whole. Not understanding the structural imbalances that persist go beyond mere words or constitutional promises. Inequality is a reflection of structural problems that exist in society and as long as they don’t disappear inequality will not.

From the perspective of a queer person, while Section 377 is gone, there is marriage inequality, and on a daily basis, people are petrified of coming out at work, because of fear of harassment or wrongful termination. They will not get apartments to rent. These are matters where the law has not even intervened and sought to give protection to people. Unless you have lived and walked in the shoes of a queer person, you don’t know what discrimination truly means.

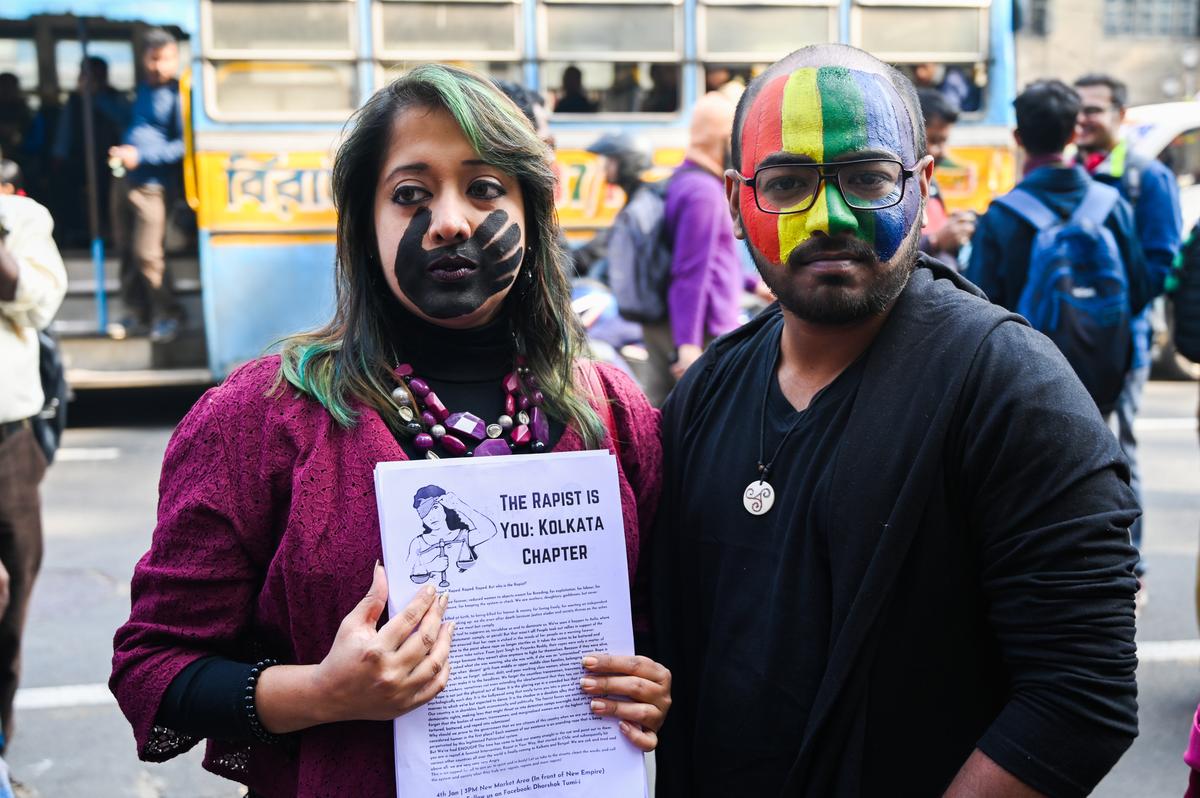

People gather at a Pride march, in New Delhi. | Photo Credit: Sushil Kumar Verma

What inspired you to write this book?

Different people try to bring about change in different ways. I’m obviously interested in fighting it because of my sexuality. But I think as a lawyer and a person who has seen injustice, not just on the grounds of sexuality, but in terms of gender, caste and religion, I feel obligated as a human being, let alone an Indian citizen, to do something about it. That’s why I’ve written this book in relatively simple language. It highlights the issues and how the courts have dealt with it in the past, and which areas still need to be examined and how far we have come.

At a Pride walk in Kolkata. | Photo Credit: Getty Images/istock

How has your journey as an openly queer lawyer contributed to writing this book?

When I was much younger I didn’t recognise my privilege. But as I grew older, I started recognising the layered inequalities. I understand how equality or the lack of it works in a legal system, which is not just made up of judges, but Parliament and the executive. And a legal system that is also a reflection of society at large. If there is discrimination somewhere else, the net result on the citizen is the same, right? I realised that if I want equality, I will have to fight for it.

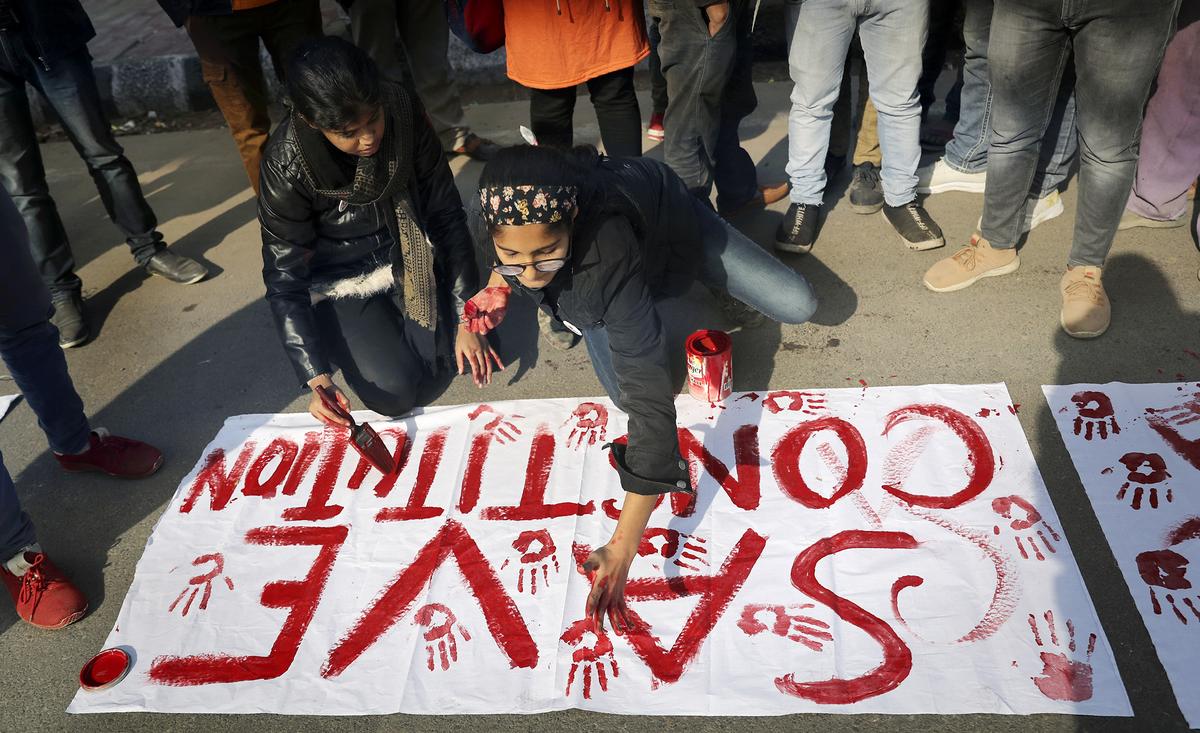

Students of Jamia Millia Islamia in New Delhi protesting against India’s new citizenship law. | Photo Credit: AP

In the backdrop of severe inequalities of class, caste, religion, etc. that exist in society, do you see a possibility of change?

A gradual change has happened. We have seen the position of women improve in business and in society. There are more women today in diverse workplaces and in higher managerial positions, a little less so in terms of caste. I think the one area most resistant to change is caste. Increasingly, religion is also falling into that slot, given the increasing polarisation that is happening in our country. But slow and gradual change is not enough. How many lives will be sacrificed at this altar of slow and gradual change? We do need a social revolution in some way.

Indian independence and the making of the Constitution was a revolutionary event. It promised a revolution but instead we got a trickle down treatment, a here-take-it-and-be-happy kind of approach and that’s not enough. We have to improve people’s lives here and now. That is our constitutional obligation.

A protest march against love jihad at Shivaji Park, Dadar. | Photo Credit: Emmanual Yogini

With anti-‘love Jihad’ laws or other such policies willfully perpetuating inequality, do you feel that the quest to attain an equal society is getting affected?

Of course. When laws are made with either malice or with an ulterior motive, two things happen. One is the fact that the law itself is discriminatory against people and they, therefore, suffer. But more importantly, a message goes down to the minority communities and all marginalised groups that you are not equal; this goes out almost like a dog whistle. There has not been sufficient analysis on how deep and grave this alleged problem of ‘love jihad’ is, other than a few instances. And by doing that it obviously demonises Muslims. Hence, it is severely detrimental to the cause of equality. Criminalising certain relationships ultimately stigmatises the community as well because everyone knows when there’s a ‘love Jihad’ law, the context behind it is the allegation that Muslim men are going after Hindu women. This is deeply problematic.

Who is Equal?; Saurabh Kirpal, Vintage, ₹699.

The interviewer is an independent writer, journalist and translator based in Allahabad. They can be reached at chittajit.mitra@gmail.com