Spacecraft powered by electric propulsion could soon be better protected against their own exhaust, thanks to new supercomputer simulations.

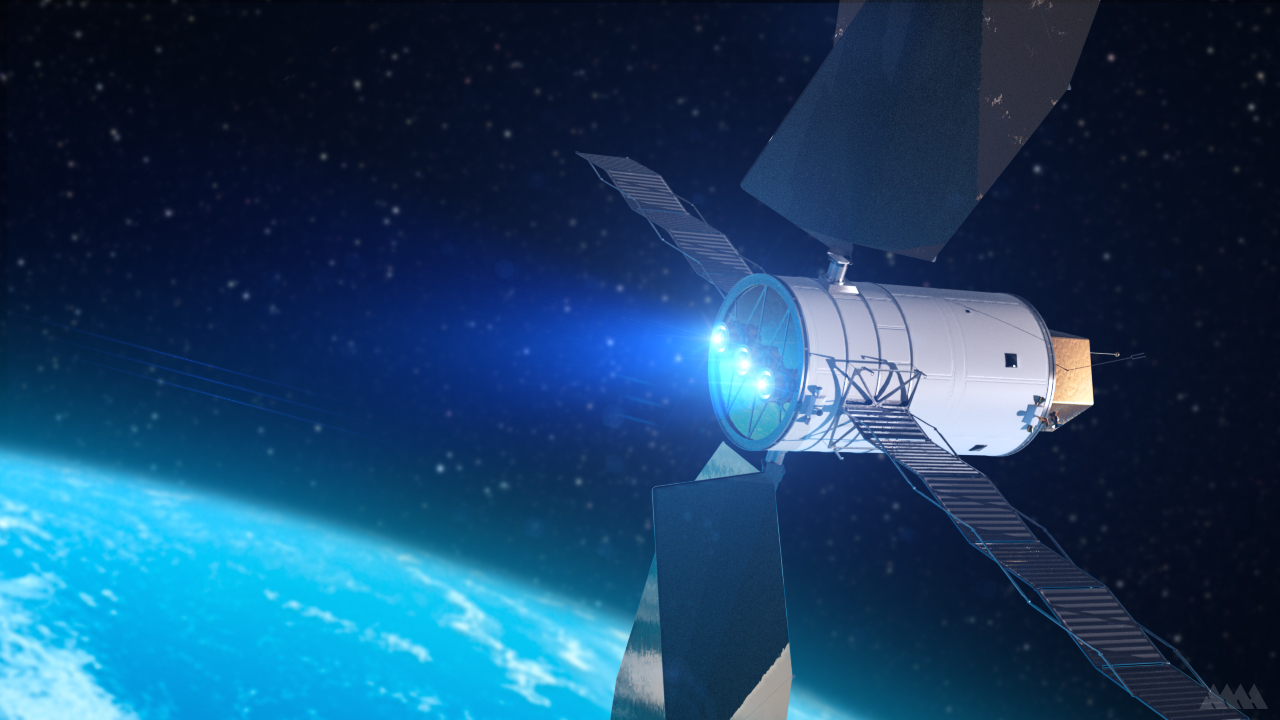

Electric propulsion is a more efficient alternative to traditional chemical rockets, and it’s being increasingly used on space missions, starting off with prototypes on NASA’s Deep Space 1 and the European Space Agency‘s SMART-1 in 1998 and 2003, respectively, and subsequently finding use on flagship science missions such as NASA’s Dawn and Psyche missions to the asteroid belt. There are even plans to use electric propulsion on NASA’s Lunar Gateway space station.

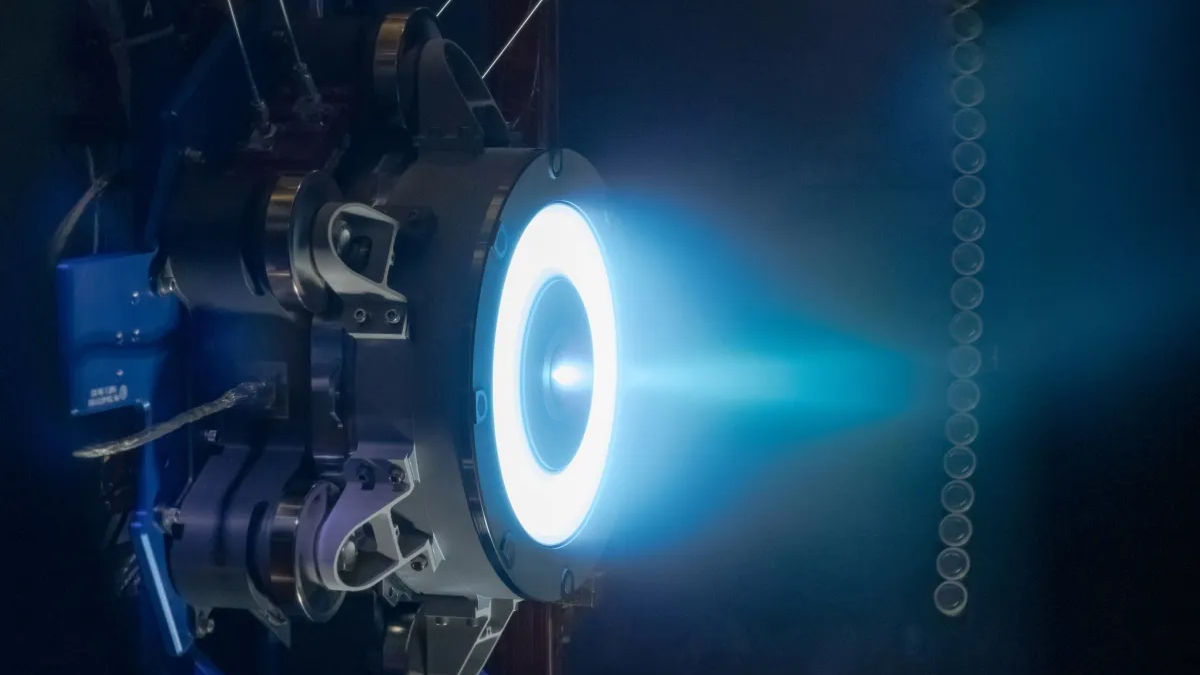

The idea behind electric propulsion is that an electric current ionizes (i.e. removes an electron from) atoms of a neutral gas, such as xenon or krypton, stored on board a spacecraft. The ionization process produces a cloud of ions and electrons. Then a principle called the Hall effect generates an electric field that accelerates the ions and electrons and channels them into a characteristically blue plume that emerges from the spacecraft at over 37,000 mph (60,000 kph). Hence an electric propulsion system is also referred to as an ion engine.

According to Sir Isaac Newton‘s third law of motion, every action has an equal and opposite reaction. The plume of ions jetting out from the spacecraft therefore acts to provide thrust. It takes a while to build up momentum, however, because, despite moving at high velocity, the ion plume is pretty sparse. The impulse generated is not as immediately forceful as a chemical rocket, but ion engines require less fuel and therefore less mass, which reduces launch costs, and ion engines don’t use up all their fuel as quickly as chemical rockets do.

Related: How an ion drive helped NASA’s Dawn probe visit dwarf planet Ceres

The energy for the electromagnetic fields is often provided by solar arrays, and hence the technology is sometimes referred to as solar electric propulsion. But for missions farther from the sun, where the sunlight is fainter, nuclear power in the form of radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) can also be used to drive the electric propulsion.

Though electric propulsion is now maturing and is being used in a variety of missions, it’s not a perfect technology. One problem in particular is that the ion plume can damage a spacecraft. Although the plume is pointed away from the probe, electrons in the plume can find themselves redirected, moving against the plume’s direction of travel and impacting the spacecraft, damaging solar arrays, communication antennas and any other exposed components. Suffice to say, this isn’t good for the probe.

“For missions that could last years, [electric propulsion] thrusters must operate smoothly and consistently over long periods of time,” Chen Cui of the University of Virginia School of Engineering and Applied Science said in a statement.

Before solutions can be put in place to protect a spacecraft from these backscattered electrons, their behavior in an ion-engine plume must first be understood, which is where Cui and Joseph Wang of the University of Southern California come in. They’ve performed supercomputer simulations of an ion engine’s exhaust, modeling the thermodynamic behavior of the electrons and how they affect the overall characteristics of the plume.

“These particles may be small, but their movement and energy play an important role in determining the macroscopic dynamics of the plume emitted from the electric propulsion thruster,” said Cui.

What Cui and Wang found was that the electrons in the plume behave differently depending upon their temperature and their velocity.

“The electrons are a lot like marbles packed into a tube,” said Cui. “Inside the beam, the electrons are hot and move fast. Their temperature doesn’t change much if you go along the beam direction. However, if the ‘marbles’ roll out from the middle of the tube, they start to cool down. This cooling happens more in a certain direction, the direction perpendicular to the beam’s direction.”

In other words, the electrons in the core of the beam that are moving fastest have a more or less constant temperature, but those on the outside cool off faster, slow down and move out of the beam, potentially being back-scattered and impacting the spacecraft.

Now that scientists better understand the behavior of the electrons in the ion plume, they can incorporate this into designs for future electric propulsion engines, looking for ways to limit the back-scatter, or perhaps confine the electrons more to the core of the beam. Ultimately, this could help missions powered by electric propulsion to fly farther and for longer, pushed by the gentle blue breeze of its ion plume.