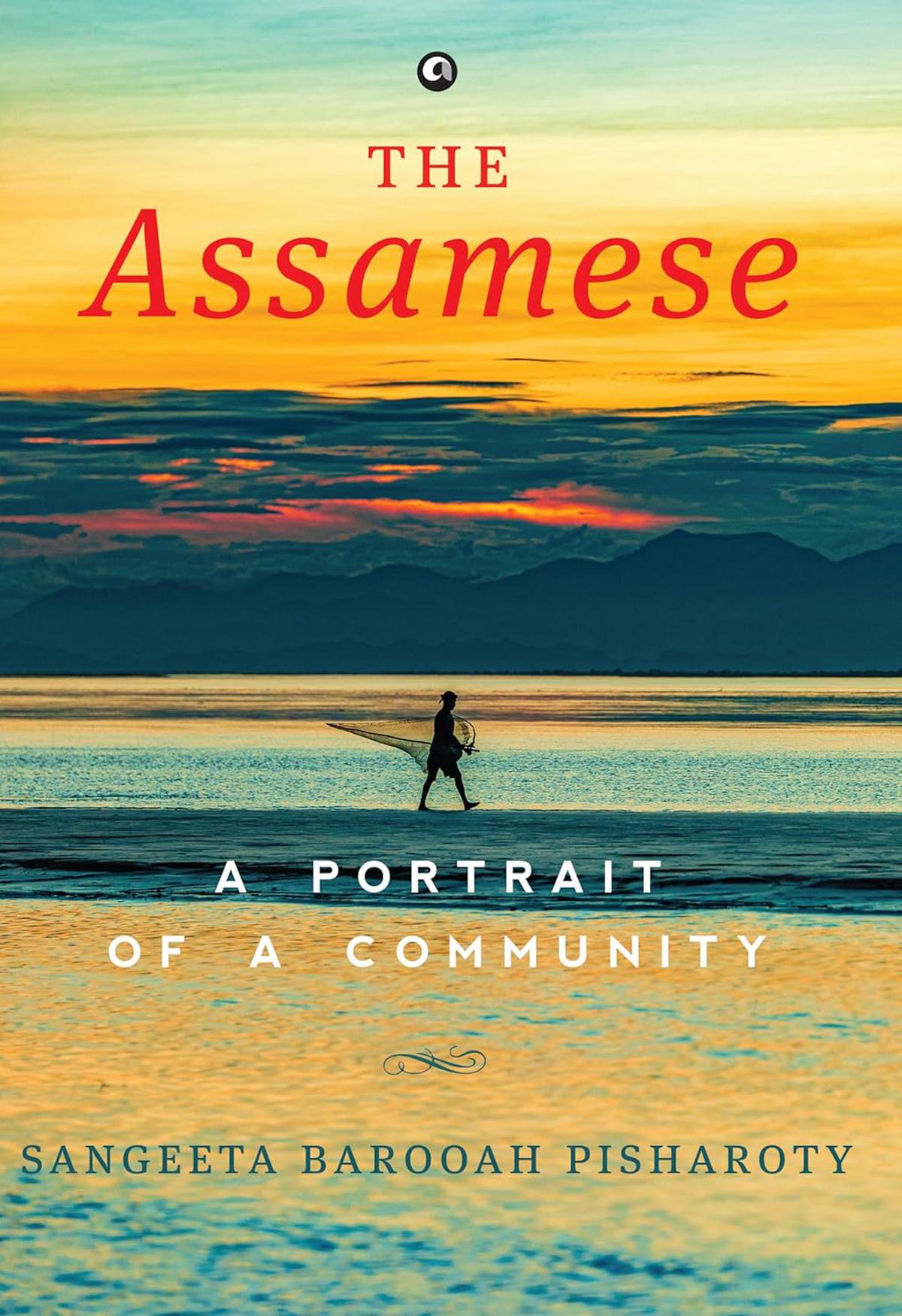

As Assam hurtles from the National Register of Citizens to the Citizenship (Amendment) Act and an ongoing Supreme Court hearing on provisions facilitating the 1985 Accord, author and journalist Sangeeta Barooah Pisharoty tackles the fundamental question of what defines its people in her second book, The Assamese: A Portrait of a Community. Edited excerpts from an interview.

Fishermen anchor their boats on the banks of the Brahmaputra following a cyclone warning in Guwahati. | Photo Credit: Ritu Raj Konwar

Just who is an Assamese is a question that has evaded political consensus for decades. Do you see an expansive administrative definition ultimately or one that excludes several communities that comprise your portrait?

The Assamese community is a rare instance of the government setting up a high-level committee to decide who comprise it rather than the people. There is of course a protracted history to it. That’s why I had to deal with the issue even though the book pertains more to the socio-cultural aspect of the community. What I’d like to particularly highlight though is that the book ends with not my definition of Assamese but with people who identify themselves as such. For instance, well-known actor Victor Banerjee, who is born Bengali, grew up in Assam, and calls himself “Ashaamer chhele” (son of Assam).

Overcrowded public ferries cross the Brahmaputra on a stormy day, in Assam. | Photo Credit: Getty Images/istock

For a few years, I’ve seen the identity of the Assamese community swerving towards a particular religion, but that has never been historically the case. The cultural greats, including Bhupen Hazarika, highlighted that the Assamese community is the product of multiple bouts of migration over the centuries. And that is what makes us.

Tribal woman during the Ali-Aye-Ligang festival in Guwahati. Ali-Aye-Ligang is one of the most vibrant festivals celebrated by the Mishing tribe of Assam. | Photo Credit: Getty Images/istock

You point to the blending of tribal and non-tribal elements in the cultural markers traditionally associated with the State and its people. Does ethnic assertion pose a threat to the composite form? After all, Assam today is a shrunken version of its earlier frontiers in the Northeast.

Why I say the Assamese community is unique is because if you look at even Manipur, the majority community does not have a tribal component. Of course after the Assam agitation, there was assertion by tribal sub-groups who felt their rights were being diluted, but culturally the bond is still inseparable — even with Bodos. One of the major features of Assamese jewellery, the rongamoni (red bead), is a tribal contribution. Even the tribal influence on Assamese language is immense. But politics closes windows rather than opening them. So, there’s a risk — what we’re seeing in Manipur is a manifestation of it.

People protesting against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA) in Dibrugarh district, Assam. | Photo Credit: Ritu Raj Konwar

What do you make of the complicated historical relationship with Bengal and Bengalis at a time Assamese sub-nationalism is being pulled towards the crossroads of religion?

We’re seeing the tilting of the Assamese identity towards a Hindu identity. But when it comes to Assamese and the Bengali [illegal immigration] question, the religion goes into the backdrop. We saw that in the anti-CAA protests. Ethnicity became more important.

Members of the 30 indigenous organisations protesting against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) in Dibrugarh district, Assam. The protest rally was organised by the All Assam Students Union (AASU). | Photo Credit: Ritu Raj Konwar

A recurring theme in the book is the patriarchy and caste hierarchies that have afflicted Assamese society, even in the Sankari tradition. Why, as you say, is it something that we don’t care to talk about?

Patriarchy is something we don’t talk about not just in Assam but the Northeast. I see it among the Nagas, even in the matrilineal Khasi society. There is a tendency in mainland India to airbrush this and talk about the rights women enjoy in the Northeast. Yes, we have more rights but within the four walls of the house. Look at the political space — so many north-eastern States are terrible in terms of giving political rights to women. At the bottom of it is unsaid, inherent patriarchy. I wanted to highlight it.

Women tea leaf pickers returning after a day’s work on the plantation, in Assam. | Photo Credit: Getty Images/istock

In the Northeast, class, community are more important than caste. But caste plays a role… in politics, and even in societal functioning. I now see a lot of intermarriages in Assam between tribals and non-tribals, upper classes and lower classes, castes… I feel very hopeful.

Assam and the Assamese are no longer unknown entities in the mainstream imagination. Does the diaspora increasingly play a role in shaping the community identity?

Historically, Assam and the Northeast have been a migrant-attracting region, but now they’re a migrant-producing one. The educated lot want to settle down outside, but there’s a fluid migrant population that’s a product of a lot of mismanagement… poor governance, plus so many bandhs and unrest. They are also representatives of Assam and the region. Most of these migrants I meet want to come back after earning some money. Somewhere, at some point, it will make a dent within the whole definition of the identity.

A crowded bazaar in Guwahati. | Photo Credit: PTI

The Assamese: A Portrait of a Community; Sangeeta Barooah Pisharoty, Aleph, ₹999.

abdus.salam@thehindu.co.in