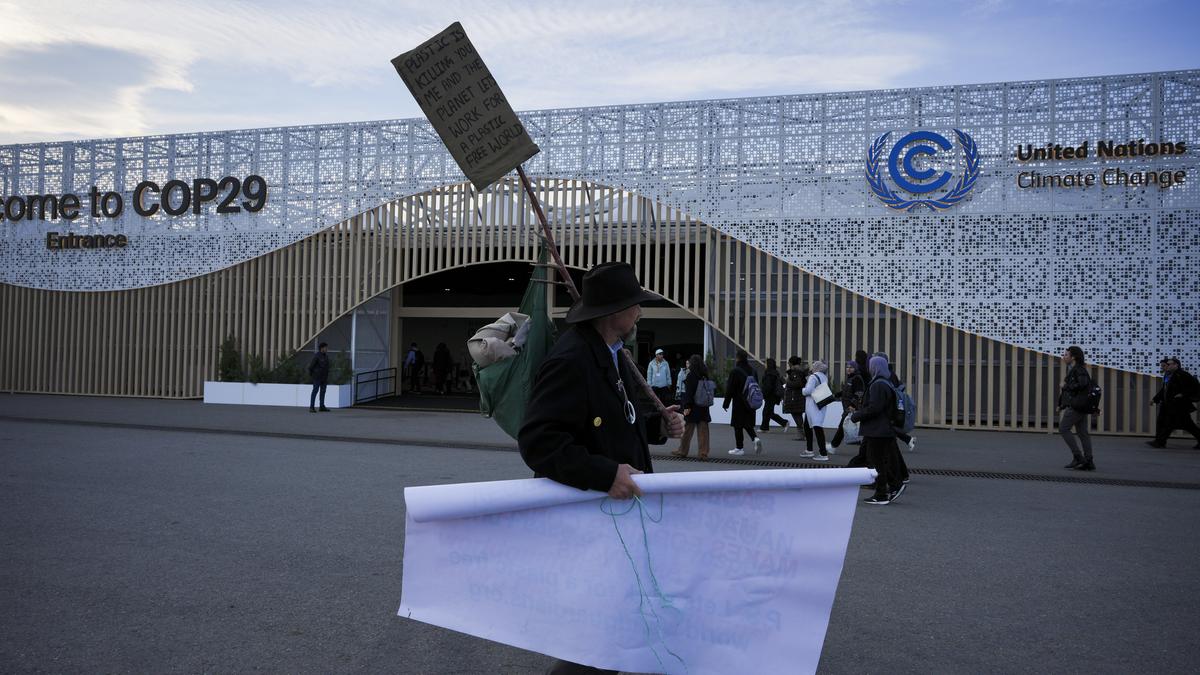

The exhaust from the planes that ferried ministerial delegates to Baku for the climate conference, which concluded on Sunday (November 24, 2024), has barely settled. Yet some of them found themselves on the red-eye to this coastal city to lay the foundations of a new United Nations-mediated treaty to end plastic pollution – and potentially the production of plastic.

On December 1, representatives from 175 countries would hope that this fifth and anticipated final round of discussions of the Intergovernmental Negotiations Committee (INC), following those in Punte Del Este (Uruguay), Paris (France), Nairobi (Kenya) and Ottawa (Canada), will result in an agreement.

Were the Busan negotiations to prove successful, next year will see a diplomatic convention where Ministers from signatory countries (parties) will likely adopt the text and set the ground for periodic meetings – akin to the annual climate Conference of Parties (COP) – to evolve a legally binding treaty to progressively weed out plastic.

For comparison, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change – the guiding climate change tackling agreement – was adopted in 1992 and entered into force in 1994. The first COP was held in Berlin in 1995.

“The historic Paris Agreement of 2015 where the world finally agreed to limit emissions to keep temperatures from breaching 2 degree Celsius took 21 Conference of Parties meetings. We cannot wait for 21 years to end plastic,” said Inger Andersen, Executive Director, United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) at a press conference on Monday (November 25, 2024).

In March 2022, in Nairobi, the United Nations Environmental Agency (UNEP’s governing body) passed a resolution to “end plastic pollution, including in the marine environment”.

Also read: South Korea’s mountain of plastic waste shows limits of recycling

While there is global consensus that plastic pollution is a problem, and several countries are enthusiastic about ways and means to encourage recycling and prohibiting certain plastics that lead to littering – India for instance has banned single-use plastic since 2022 – many of them prefer to drag their feet on actually limiting plastic production. Many of these countries are either petro-states or those that have significant industries that manufacture plastic polymers.

Negotiations in the week ahead will centre around a ‘non-paper’, a document put forward by the INC Chair Luis Vayas Valdivieso, that serves as a synthesis of the common ground that countries have seemingly achieved in the previous negotiations since 2022.

Representatives from India, in their intervention during plenary discussions, said that it was agreed on accepting the non-paper as a base text but was opposed to certain references to “primary plastic polymers”.

The committee is expected to aim for resolution on four broad themes: plastic products, chemicals of concern as used in plastic products, product design, and production/supply and related aspects; plastic waste management, emissions and releases, existing plastic pollution, including in the marine environment, and just transition; finance, including the establishment of a financial mechanism, capacity building, technical assistance and technology transfer, and international cooperation; and implementation and compliance, national plans, reporting, monitoring of progress and effectiveness evaluation, information exchange, and awareness, education and research, according to a bulletin by the International Institute for Sustainable Development.

A legal drafting group is expected to begin work on the initial and final provisions of the text before considering the substantive and operational aspects of the new treaty, it added.

Published – November 25, 2024 08:27 pm IST