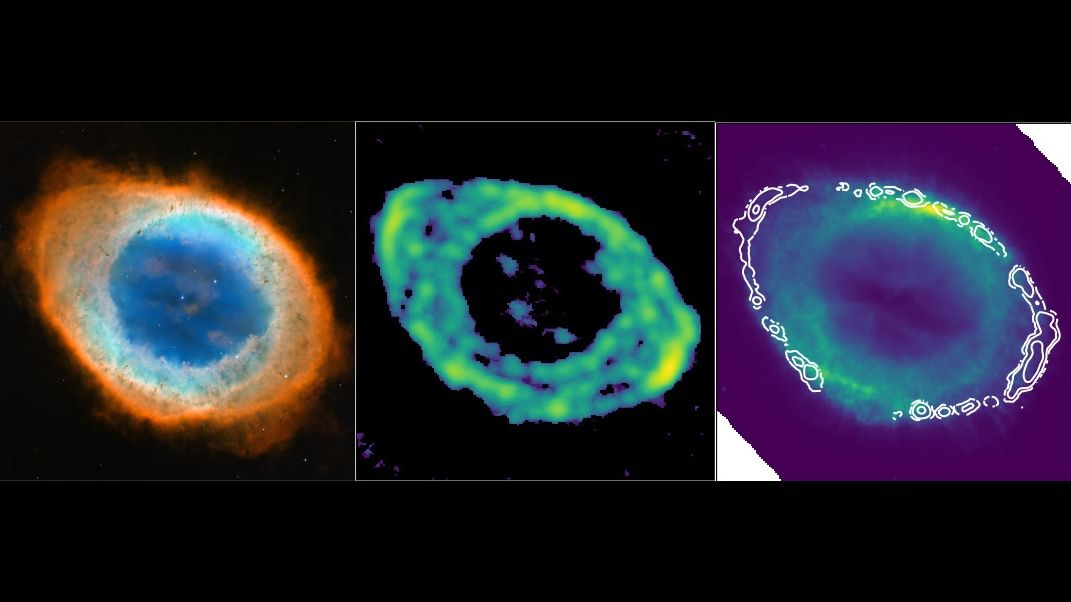

One of the most photographed objects in the night sky is the Ring Nebula, wreckage of a bygone sun-like star about 2,000 light-years from Earth. Its striking, smoke-ring-like appearance has both awed and puzzled astronomers, who have long debated whether this remnant truly takes on a ring shape or if its appearance is merely an illusion created by our viewpoint in space.

Fresh observations of the Ring Nebula have now traced the motion of gas molecules along its border, allowing astronomers to tease out its structure in greater detail. The results show the remnant is shaped less like a perfect ring and more like a barrel, with our viewpoint aligned directly down its poles, Joel Kastner of the Rochester Institute of Technology told reporters on Tuesday (Jan. 14) during the 245th American Astronomical Society (AAS) press conference in Maryland.

We are staring “right down the barrel of it, which is really quite surprising to me — we’re just lucky,” he said, noting the findings provide essentially “a brand new view of an old astronomical friend.”

These findings help scientists better understand the processes that sculpt complex planetary nebulas, which, despite their name, have no actual connection to planets. They are actually the remnants of stars similar to ours that died long ago. The misnomer arose because of these nebulas’ planet-like appearance when viewed by early astronomers through small telescopes.

“Planetary nebulae were once thought to be simple, round objects with a single dying star at the center,” astronomer Roger Wesson of Cardiff University said in a previous statement. “It begs the question: how does a spherical star create such intricate and delicate non-spherical structures?”

In an attempt to find out, last year, Kastner and his colleagues used the Submillimeter Array (SMA) — a network of radio dishes atop Mauna Kea in Hawaii — to gather high-resolution images of the Ring Nebula.

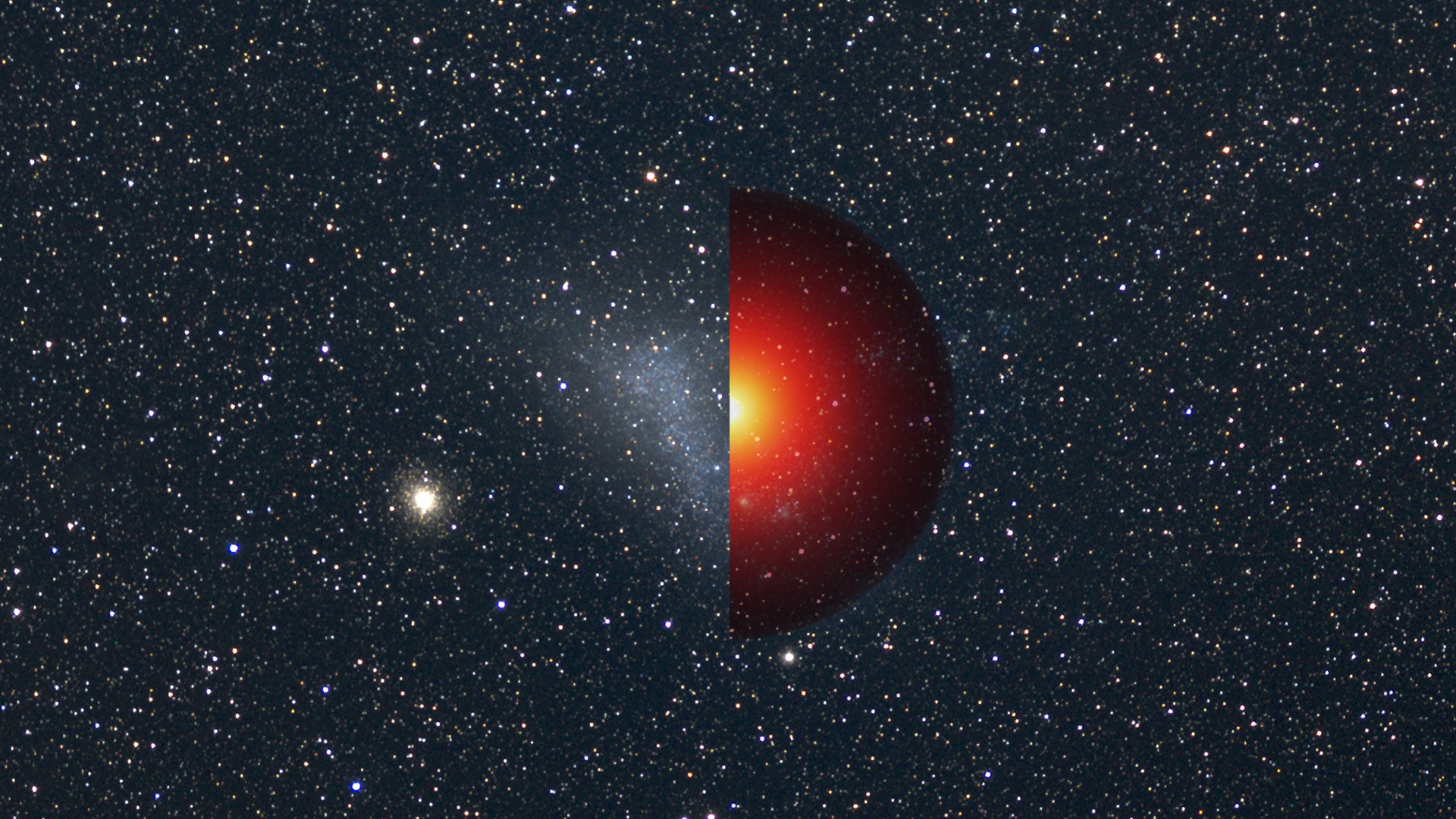

Specifically, they mapped movements of carbon monoxide gas molecules that outline the nebula. Kastner said tracking the velocities and locations of those molecules, which were thrown out by the dying, sun-like star that created the nebula about 4,000 years ago, revealed its 3D shape in detail — something that cannot be determined from collapsed views by telescopes, even powerful observatories like the Hubble and James Webb space telescopes.

In addition to helping the researchers nail down the nebula’s ellipsoidal structure, the 3D model also confirmed that the stellar corpse of the bygone star known as a white dwarf, which is seen as the tiny white dot within the nebula, is indeed located at its center.

“That was not a foregone conclusion,” Kastner said during the AAS press conference. The white dwarf appears slightly off-center in many telescope images; this, however, could be due to our viewing angle and the remnant’s slightly misaligned “poles,” rather than the star’s position itself, Kastner explained.

Recent exquisite images from the James Webb Space Telescope had revealed several concentric arcs just beyond the outer edge of the main ring, which seem to have formed every 280 years.

But there is no obvious reason for why that would occur with such precise regularity, leading astronomers to posit an unseen companion star likely orbits the central white dwarf. That hidden star, which astronomers estimate should be at least as far from the central star as Pluto is from the sun, would have sculpted material shed by the dying star to result in the stunningly complex nebula we see and love today.

Indeed, in the new observations, Kastner and his team observed “holes” in the nebula, which they attribute to faster, younger outflows shed by the hidden companion star. The presence of a stellar sibling to the central star “will fiddle badly” with the simple, one-star scenario that forms these nebulas, Kastner said during the press conference.